Artificial Intelligence will be helpful and convenient in many ways, but I do not want to read the words of an artificial poet. I will not chew on plastic, no matter how much it may look and taste like bread. I shun the warmth of an artificial sun. AI may provide the impression of poetry, and indeed satisfy our sensory organs, but it cannot reproduce its essence, the recognition of ourselves in the other which achieves the strengthening and expansion of our consciousness.

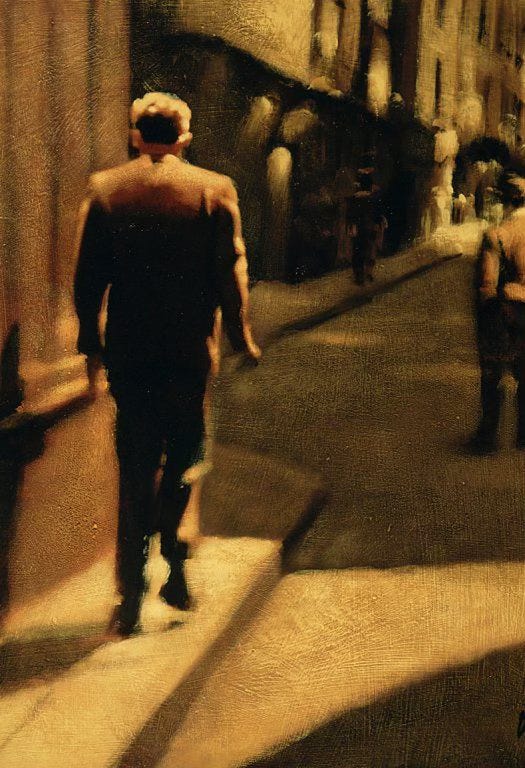

Hello all. I have been away a little while. Indeed a good while longer than expected. There are a few reasons why I have taken a longer than expected break, some of which I may detail for you all in the future. Suffice to say, like Keats in his poem of same title, I felt as ‘one who has been long in city pent’. Like the nineteenth century London of Keats’ day, my internal city was often full of smog and loud noise, as often is the case within the City of Man (to borrow from Augustine). But amid the grey mist there was always a lantern’s glow that led the way forward, however faint and dimly lit.

Sometimes, the fact of our being lost in this fog, when others appear to be walking bright and clear in the afternoon glow, can feel a little unfair. I know I have often felt like the speaker of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, The Day is Done (1844), looking on in ‘sadness and longing’:

I see the lights of the village Gleam through the rain and the mist, And a feeling of sadness comes o'er me That my soul cannot resist: A feeling of sadness and longing, That is not akin to pain, And resembles sorrow only As the mist resembles the rain.

Yet even in our inadequacies, our lack of energy that can feel like spiritual death, the wonderful thing about poetry is that it never dies. ‘The poetry of earth is never dead’, wrote Keats, in the opening line of his sonnet, On the Grasshopper and Cricket (1818). Even in the quiet gloom of evening, ‘when the frost / Has wrought a silence’, there still sings ‘The cricket’s song, in warmth increasing ever’. Coleridge, in his poem, Frost at Midnight (1798), wrote of the ‘strange / And extreme silentness’ that suits poetic musing, ending his poem with an image of ‘silent icicles, / Quietly shining to the quiet Moon’. It is in this same Quietude that I have rediscovered the path of writer, scholar, and poet.

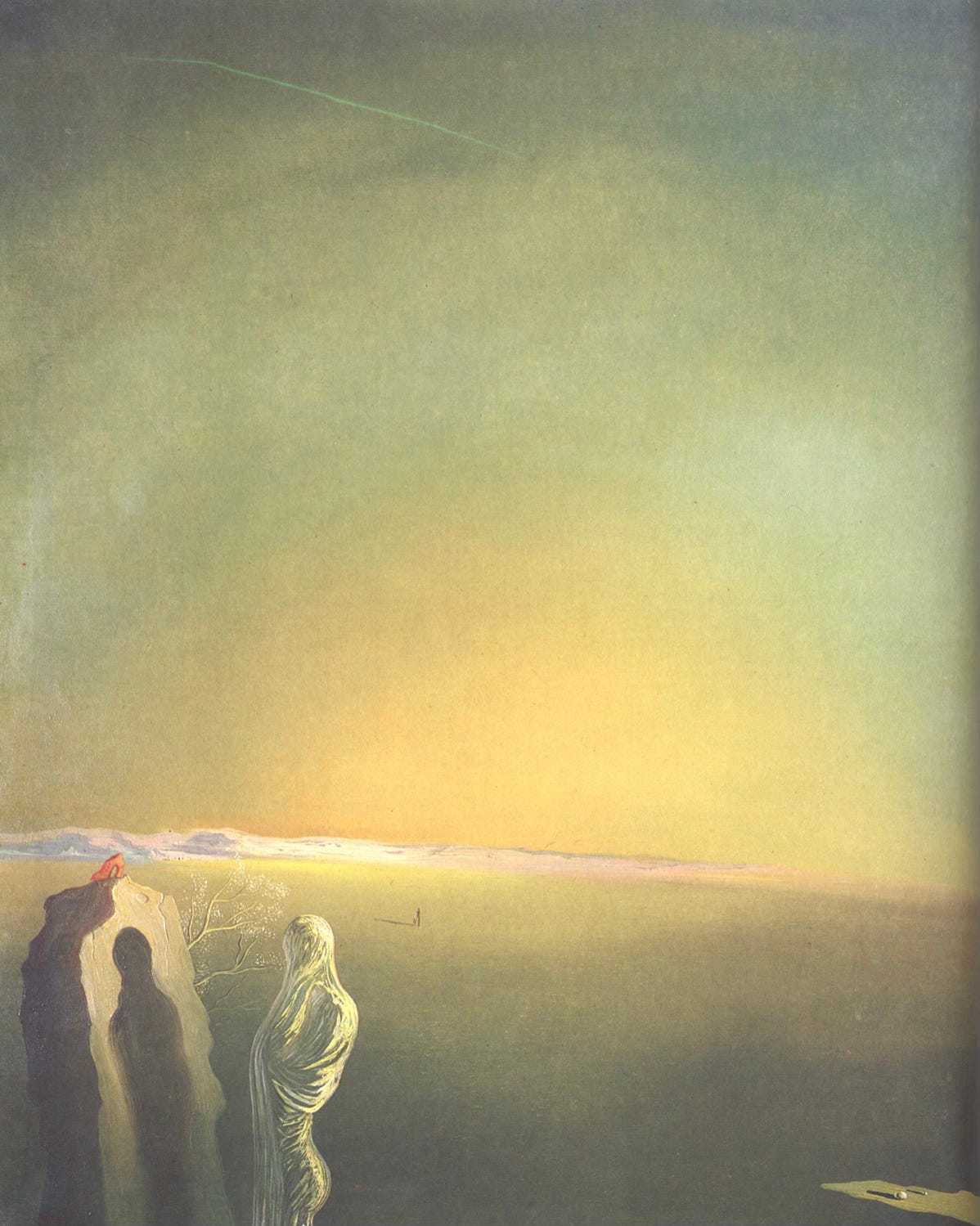

For me, the art of reading and writing about poetry and literature is often about noticing glimmers and glimpses of the divine in the everyday; to catch onto moments of grace in the commonplace, whether in nature or in each other. That is why AI can never wholly replace the writer, priest, or psychologist. A machine, however complex are its neural networks and algorithmic makeup, cannot experience the fleeting feeling, the sudden ahah! of recognition one feels when reading a great book or poem, or when speaking with another human about our deepest dreams and fears. This recognition is the very thing that sets the human soul on fire, carrying us through our longest nights.

An algorithm cannot, as in Keats’ sonnet, On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer (1816), feel that ahah! moment, ‘like some watcher of the skies’ that has found a ‘new planet’; or when ‘stout Cortez […] with eagle eyes’ looked out upon the Pacific, sharing a ‘wild surmise’ among his crew as new land appeared on the horizon. This is the feeling of great literature, how it impacts and raises our consciousness. The quick inhalation of breath—and holding—as surprise takes hold. I mean enchantment: an encounter with the other which somehow involves a renewed encounter with the self.

Can an AI experience silence and contemplation? The very prerequisite for human ingenuity and creative expression? The spiritual writers and mystics of the western tradition have long recommended the path of silence as a way to hear God’s voice, to retreat into the desert or the mountains to hear more closely the tenor and rhythm of the divine Plan. In my own silence, I have come to find some insights about myself and the world that I otherwise would not have felt.

AI will be helpful, necessary, convenient, a world-changer, but I do not want to read the words of an artificial poet. I will not chew on plastic, no matter how much it may look and taste like bread. I shun the warmth of an artificial sun. AI may provide the impression of poetry, and indeed satisfy our sensory organs, but it cannot reproduce its essence, the recognition of ourselves in the other which achieves the strengthening and expansion of our consciousness. AI should not write our stories for us.

I know that I am not the only student of the humanities that has felt the dread of the AI revolution. When reflecting on our roles as writer, scholar, poet, there is now always an underlying sense of tension and uncertainty about our future within society, a tension that simply did not exist even a few years ago before the sudden advent of the Large Language Model. We know that if we had been born a decade earlier there would be no doubt whatsoever about the propriety or worth of our vocation. The prospect of continuing through to a post-graduate education in the humanities, a masters or a PhD in some obscure subject of inquiry, would not only be expected, but exciting! And now we are beset with a question that past generations have not had to contend with: will there be a place for me?

Frankly, I wish that we did not have to contend with this uncertainty. And yet, we remember the words of the wise wizard, in Tolkien’s Fellowship of the Ring:

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

In light of these advancements in AI, no doubt there will be many that eventually lay aside the pen and take up work in other sectors that are more friendly to our shifting economic and societal landscape. I do not judge these acts of self-preservation for a moment (even now we feel the fault lines begin to rumble), and it may indeed be a sensible thing to do, especially while one is young and able to learn new skills.

But for those of us who choose to stay, who see and acknowledge the great, grey wave of algorithmic plastic with clear eyes, and yet choose to continue with our creative careers and hobbies, can anyone deny that there is now a heightened sense of humanity—even heroism—in our pursuit? When I think of Silicon Valley billionaires setting the tone and tenor for our future debates around moral and ethical questions, through their direct influence upon AI algorithms, I feel a certain angst and unease that is hard to shake. Joan of Arc is often quoted to have said, in the face of opposition: ‘I am not afraid. I was born for this.’ To grapple with civilisational change, to witness the evolution of what it means to be human, and to guard this evolution from the undue influence of technocrats and billionaires: as writers and readers, we were born for such a time as this.

And so, even amidst all the uncertainty that the AI revolution poses for us with interest in the humanities, I somehow feel renewed in my path as a writer and a storyteller, confident that within my work there dwells the residual glow of the divine spark that rests within each of us, and will indeed survive long after our body has decayed. Taking up arms against a sea of troubles never felt so rewarding. After all, I am only following in the footsteps of Longfellow, as he writes in the fourth stanza of The Day is Done:

Come, read to me some poem, Some simple and heartfelt lay, That shall soothe this restless feeling, And banish the thoughts of day.

"Can an AI experience silence and contemplation? The very prerequisite for human ingenuity and creative expression?"

This made me think about the brave it takes to be bored today. growing up boredom was presented to me as something to be avoided or uncool. but I find that I forget myself if I don't have silence, or speak out my thoughts and feelings on an evening walk. it's through this silence I rediscover myself and ask questions on my own conscience; where my friendship with nature and my Creator is renewed. AI simply cannot imitate that feeling and that's why I too dread it's rapid growth.

Thank you for writing again Andrew. Needles to say we've all missed you sharing your thoughts with us!

Beautifully written and thought provoking. Staying on the path of quiet contemplation and the softly written word is a noble calling.