The Secondary World of storytellers, artists, and poets renews the Primary World of the day-to-day. In reading great literature, especially high fantasy and mythology, we see once again the drama of our world as we might have seen it when the world was young, and each event was marvellous in its newness.

Hello all. It is great to be back writing about Tolkien once again. Today’s article will focus upon his enchanting little poem, Bilbo’s Last Song. I will provide the poem in full and also my thoughts below. At the end of this letter, I also have a few thoughts on Tolkien’s concept of Recovery, and how the reading of Fairy Stories can help us to see the world and our lives in new and enchanting ways (or, perhaps, in old ways). There are also numerous paintings below from Tolkien illustrator, Ted Nasmith, which I hope you enjoy!

Day is ended, dim my eyes, but journey long before me lies. Farewell, friends! I hear the call. The ship's beside the stony wall. Foam is white and waves are grey; beyond the sunset leads my way. Foam is salt, the wind is free; I hear the rising of the Sea. Farewell, friends! The sails are set, the wind is east, the moorings fret. Shadows long before me lie, beneath the ever-bending sky, but islands lie behind the Sun that I shall raise ere all is done; lands there are to west of West, where night is quiet and sleep is rest. Guided by the Lonely Star, beyond the utmost harbour-bar I'll find the havens fair and free, and beaches of the Starlit Sea. Ship, my ship! I seek the West, and fields and mountains ever blest. Farewell to Middle-Earth at last. I see the Star above your mast!

Bilbo’s Last Song serves as an epilogue of sorts to Tolkien’s classic trilogy, The Lord of the Rings. The poem’s three stanzas follow Bilbo Baggins as he embarks on a final journey into the West, the land of Valinor, sometimes referred to as The Undying Lands. It is home to the race of immortal Valar, and also of certain Elves who have been allowed to reside there, on account of their own immortality. It is a place similar to Asgard in the Norse legendarium. Around 1968, Bilbo’s Last Song was given as a gift to Tolkien’s secretary, Joy Hill, who chanced upon the forgotten poem while helping the professor unpack his various books and papers after moving from his Oxford abode. We know, of course, from The Lord of the Rings, that Bilbo’s nephew, Frodo, as well as Gandalf, Elrond, and Galadriel, also take part in this journey across the sea, and that Sam, Merry, and Pippin, are there to see them off before returning to their homes in the Shire.

The poem begins with a world-weary Bilbo setting out on his final adventure. The day has ended, and here begins his journey:

Day is ended, dim my eyes, but journey long before me lies.

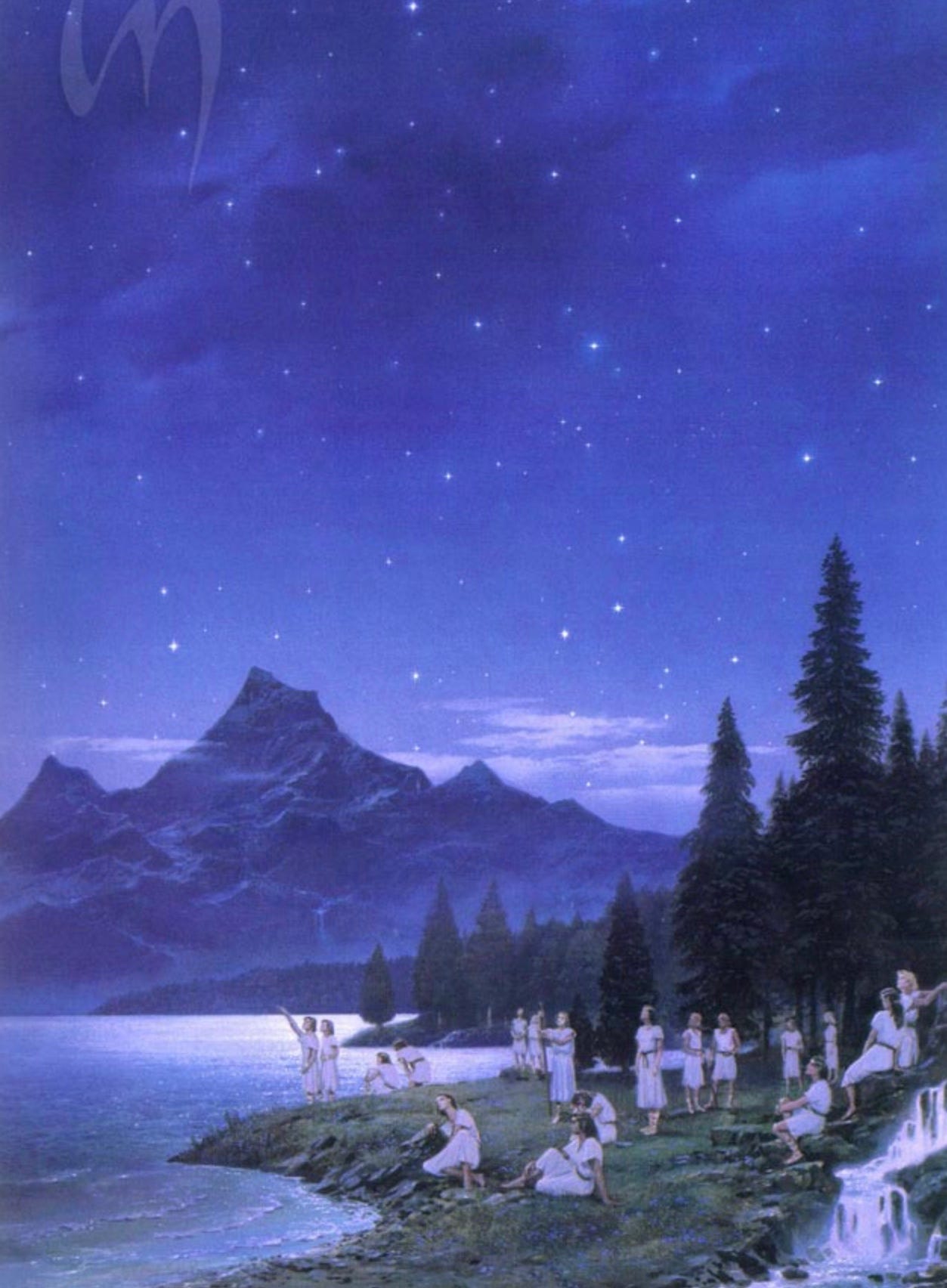

Day is ended. It would seem that Hobbits preferred to set out for their travels in the evening. Bilbo, in the Fellowship of the Ring, set out for Rivendell after his long-expected party on ‘a fine night, [when] the black sky was dotted with stars’ (p. 41). And some years later, as Frodo and his friends would set out to follow in his footsteps:

The sky was clear and the stars were growing bright. 'It's going to be a fine night,' he said aloud. 'That's good for a beginning'.

That’s good for a beginning. In Bilbo’s Last Song, we can’t help but feel that this story’s beginning is also an ending. The fading day and gathering dark establish the poem with an aura of mortality and loss, but not without hope for the future:

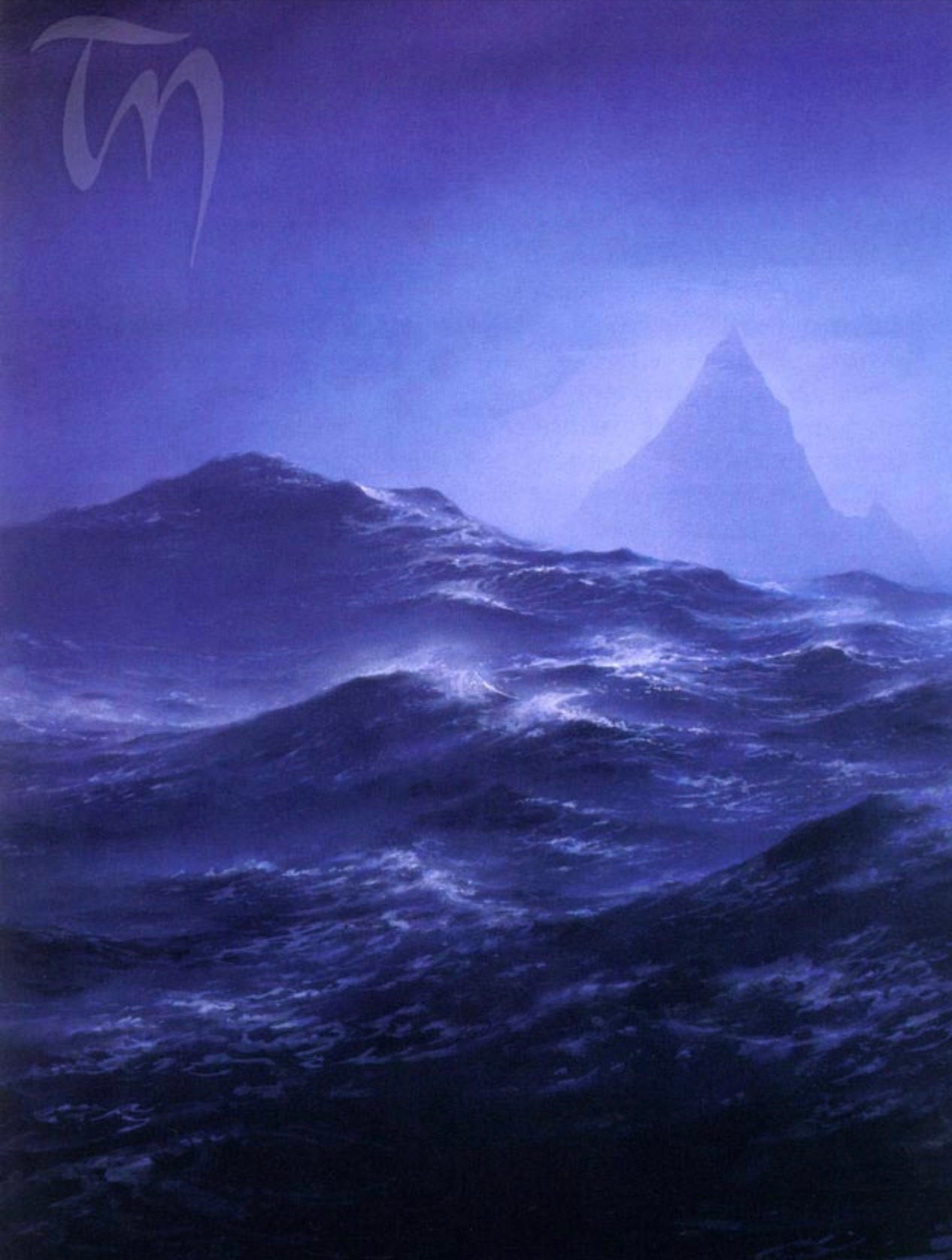

Farewell, friends! I hear the call. The ship's beside the stony wall. Foam is white and waves are grey; beyond the sunset leads my way. Foam is salt, the wind is free; I hear the rising of the Sea

I hear the call. This is the same call to adventure—a call towards danger and chance—that Bilbo had so keenly felt all those years before as he listened to a company of dwarves hum ancient songs in his living room, songs that that spoke of ‘dungeons deep and caverns old’. A spirit of adventure rose up in Bilbo’s breast as he heard the ‘deep-throated singing of the dwarves in the deep places of their ancient homes’:

As they sang the hobbit felt the love of beautiful things made by hands and by cunning and by magic moving through him, a fierce and a jealous love, the desire of the heart of dwarves. Then something [...] woke up inside him, and he wished to go and see the great mountains, and hear the pine-trees and the waterfalls, and explore the caves, and wear a sword instead of a walking stick. The Hobbit (1937), p. 22).

Bilbo’s Last Song intimately connects this calling with the Sea. Already in the first stanza, as the hobbit is preparing to embark on his final journey, he ‘hear[s] the rising of the Sea’, a sound heard not in the physical plane of sense and feeling—he was not yet near the sea-port of the Grey Havens—but a deeply felt sound within his mind’s eye, or poetic faculty. Frodo, too, felt this deep instinct, this recognition of a mysterious calling, rising in himself in the early chapter’s of The Fellowship of the Ring. Frodo ‘began to feel restless, and the old paths seemed too well-trodden. He looked at maps, and wondered what lay beyond their edges…’ (52). Philosopher and Tolkien scholar, Peter Kreeft, commenting on this passage, notes that ‘it is not exactly clear what is being desired here, but it is “something more” […] a ‘longing [which] sweeps through The Lord of the Rings like a wind over the sea.’ (Kreeft, 112). It is towards this something more that the whole of Tolkien’s corpus is oriented.

In saying ‘Farewell!’ to his friends in Middle-earth, Bilbo is not only moving away from his old life, but also towards a new home, an unfading home in that hallowed place across the sea:

Farewell, friends! The sails are set, the wind is east, the moorings fret. Shadows long before me lie, beneath the ever-bending sky, but islands lie behind the Sun that I shall raise ere all is done; lands there are to west of West, where night is quiet and sleep is rest.

Even on this final journey, there are still tasks to complete; still effort to be exerted; still a trail to follow. Upon his arrival in that place across the Sea, Bilbo fully expects that there are still other realms to discover—‘islands […] that I shall raise ere all is done’—and that there are dimensions to reality that are far wider and broader than he had yet experienced in the land of mortals. And until then, even on this journey to the western shores, still there are ‘Shadows long before […] and beneath’. Yet, as is so often felt in Tolkien’s writings, an enduring hope propels and sustains the journeyman. For the aged hobbit, the object of this hope is a deep and abiding rest. The free wind and flapping sails provide a foretaste of this coming convalescence in the Undying Lands.

The beginning of the third and final stanza recalls the traditional image of the Wise Men being guided to Bethlehem by the miraculous ‘star in the east’ (Mt 2:9):

Guided by the Lonely Star, beyond the utmost harbour-bar I'll find the havens fair and free, and beaches of the Starlit Sea.

I’ll find the havens fair and free. To be sure, the single ‘Lonely Star’ acting as a guide is reminiscent of the Star of Bethlehem, but it is primarily a reference to Varda, Lady of the Stars. Tolkien scholar, Peter Kreeft, refers to Varda as a kind of ‘guardian angel’ figure, inspired by veneration of the Virgin Mary in the Catholic devotional tradition. Frodo calls for her aid (or intercession) under the title, ‘Elbereth, Gilthoniel!’ (which means Elbereth, Starkindler) when he is attacked by the Nazgul on Weathertop. This hymn to Elbereth was sung in Rivendell, in The Hall of Fire, while Bilbo and Frodo stayed there together for a time, before the Ring’s journey South. Frodo ‘stood still enchanted, while the sweet syllables of the Elvish song fell like clear jewels of blended word and melody’. After both Frodo and Bilbo had left the Elvish hall, Bilbo bid farewell to his nephew for the night:

Good night! I'll take a walk, I think, and look at the stars of Elbereth in the garden. [Fellowship of the Ring, Book II, Many Meetings]

Samwise later recalls the Lady’s hymn in Shelob’s Lair, remembering ‘the music of the Elves as it came through his sleep in the Hall of Fire in the house of Elrond’:

A Elbereth Gilthoniel o menal palan-diriel, le nallon si di'nguruthos! A tiro nin, Fanuilose! O Elbereth Starkindler from heaven gazing-afar, to thee I cry now in the shadow of death. O look towards me, Everwhite.

Considering the lines above, it is hard not to feel Varda’s presence in Bilbo’s Last Song, the lonely star guiding Bilbo on his final journey.

Finally, as Cirdan the shipwright traversed his ship across the sea, Bilbo shouts excitedly in wonder and relief as he sights the shores of the Undying Lands:

Ship, my ship! I seek the West, and fields and mountains ever blest. Farewell to Middle-Earth at last. I see the Star above your mast!

In a recent talk on the power of storytelling in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien scholar and poet, Malcom Guite, reflects on how this classic tale can serve as a source of “refuge, refreshment, and renewal”. In his famous lecture, On Fairy Stories (1939), Tolkien referred to his literary creation as a ‘Secondary World’ of ‘sub-creation’ (Tolkien, On Fairy Stories, 52), distinct but not wholly seperate from the Primary World in which we reside.

The Secondary World of storytellers, artists, and poets renews the Primary World of the day-to-day. Curiously, however, the Secondary World enchants the primary world not by affecting change or transformation from the outside, but rather by allowing us to see what is already here with new eyes—or, rather, with old eyes. In reading great literature, especially high fantasy and mythology, we see once again—albeit only in glimmers and rays—the drama of our world and of human life as we might have seen it in the dawn of society, or in the newness of childhood, when the world was still young and each event was marvellous because it was new; when our experience of life, consciousness, and nature was still filled with wonder and awe.

C.S. Lewis, in his review of Fellowship of the Ring, wrote that ‘what we chiefly escape’ in immersing ourselves in the world of imagination ‘is the illusions of our ordinary life’. Indeed, it is the humdrum and the tiredness of the day-to-day which is the illusion, and any sense of escapism that we experience in reading great stories is a flight toward, not away, from reality. Thus, the strange feeling of comfort and enchantment that we experience when reading Tolkien is enchanting precisely to the degree that it reminds us of who and where we really are. This is what Tolkien meant when he spoke of the primary purpose of faery story being ‘recovery’:

[W]e need recovery. We should look at green again, and be startled anew (but not blinded) by blue and yellow and red...Recovery (which includes return and renewal of health) is a re-gaining—regaining of a clear view...'seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them'—as things apart from ourselves...We need...to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness....This triteness is really the penalty of 'appropriation':...We say we know them. They have become like the things which once attracted us by their glitter, or their colour, or their shape, and we laid hands on them, and then locked them in our hoard, acquired them, and acquiring, ceased to look upon them.

- Tolkien, On Fairy Stories (p. 67).The recovery of a clear view. The above passage serves well to contextualise this beloved quote from Tolkien, given in the same lecture:

It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.

(Tolkien, On Fairy Stories, Quoted by Kreeft, p. 84).May we all experience a similar recovery and renewal of our Primary Worlds. In The Two Towers, as Frodo and Sam climbed the dreaded stairs of Cirith Ungol in Mordor, Frodo spoke of his increasing despair: ‘I don’t like anything here at all’, he said, ‘step or stone, breath or bone. Earth, air and water all seem accursed. But so our path is laid.’ Sam’s responds by recalling ‘The brave things in the old tales and songs […] the tales that really mattered’, where the characters ‘had lots of chances, like us, of turning back, only they didn’t.’ Sam then asks a question that is also our question, and the question of all those who have come before us, and all who will come after: ‘I wonder what sort of tale we’ve fallen into?’ (Tolkien, The Two Towers, 321).

Works Consulted:

Day, David. An Encyclopaedia of Tolkien: The History and Mythology That Inspired Tolkien’s World. San Diego: Canterbury Classics. 2019.

Kreeft, Peter. The Philosophy of Tolkien. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. 2005.

J.R.R. Tolkien. On Fairy Stories. Edited by Verlyn Flieger & Douglas A. Anderson. London: Harper Collins. 2008.

J.R.R. Tolkien. Bilbo’s Last Song. Illustrated by Pauline Baynes. Knopf: New York. 2002.

J.R.R. Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. London: Harper Collins. 1991.

J.R.R. Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. London: Harper Collins. 1991.

J.R.R. Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. London: Harper Collins. 1991.

J.R.R. Tolkien. The Hobbit. London: Harper Collins, 1991.

C.S. Lewis’ Review of The Fellowship of the Ring: ‘The Gods Return to Earth: C.S. Lewis’ Review of The Fellowship of the Ring’, on TheOneRing.net

Malcom Guite, talk on Tolkien’s storytelling:

You have some really vivid insights! For me, there is an undeniable feeling of death in the imagery of going over the sundering seas to the West. But Tolkien was imbued with a flavor of Christianity which denies the nullity of death and replaces it a transition to a higher state: "And then it seemed to him as in the house of Bombadil, the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise." C.S. Lewis does something similar in the last book of the Narnia series. And so does George MacDonald in the last chapters of "Lilith". I wonder, since the Christian mythos was so real to Tolkien, if writing LOTR wasn't an act of "recovery", to re-inspire the awe he felt from his religion.

Reprises Tennyson’s Ulysses and a little Second Timothy. Wonderful article.