The constancy of the ‘Bright star’ is also the eternity of the lover’s union, so ecstatic in feeling it is wished to endure, even ‘to death’. The ‘moving waters’ along the shore are also the ‘soft fall and swell’ of his lover’s breast; and the ‘soft-fallen’ snow resting upon the mountain side is also the poet’s cheek, ‘pillowed upon’ his fair love.

The memorable sonnet, Bright Star, by John Keats, was probably written in February of 1819, although there is an interesting case to make that this was the last poem he wrote before his death, according to a contemporary witness. This is one of Keats’ most well known and universally loved sonnets, and it is easy to see why.

There is some debate about who this poem is addressed to. It could be either his lover at the time, Fanny Brawne, or another lady, Isabella Jones, with whom he had previous relations, and who scholars have recognised as having played a pivotal part in the poet’s sexual development. Keats scholar, Robert Gittings, notes the influence of both women upon the sonnet, thought it is probably nearest the mark to suppose that it is not addressed specifically to either one, but is rather ‘a summing-up of Keats’s conflicting thoughts at that time on the claims of life and love on the poet’s being.’ (Gittings, 389).

The memorable image of this ‘Bright star’ seems to have come from a visit to Lake Windermere in Northwest England (where William Wordsworth lived), in June of 1818. The following remarks are from a letter to his younger brother, Tom Keats, on June 25-27, 1818:

[...] the two views we had of it [Lake Windermere, where he had just dined, and was now writing beside] are of the most notable tenderness—they can never fade away—they make one forget the divisions of life; age, youth, poverty and riches; and refine one's sensual vision into a sort of north star which can never cease to be open lidded and steadfast over the wonders of the great Power. (Gittings, Letters, 101, emphasis added).

Open lidded, stedfast, never fading. These are all descriptions that made their way into Keats’s sonnet. The literary influence upon even these words seem to go back further, to William Wordsworth’s poem, The Excursion (1814), upon which Keats remarked that it was among the ‘three things to rejoice at in this Age’ (Gittings, Letters, 48):

Chaldean Shepherds, ranging trackless fields, Beneath the conclave of unclouded skies Spread like a sea, in boundless solitude, Looked on the Polar Star, as on a Guide And Guardian of their course, that never closed His stedfast eye. (The Excursion. Bk IV, II. 690-5).

Dr. Octavia Cox, to whom I am indebted for the knowledge of the above influences, has said that there is a significant reworking (even a repudiation) of Wordsworth’s sense of the Sublime in Keats’s sonnet, including the character of the star itself, reflecting the shift in emphasis that took place from the first generation Romantics (Wordsworth, Coleridge) to the second generation (Keats, Shelley, Byron). But this reworking will become more evident a little later, as we approach the sonnet’s end.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art—

At the outset, it is important to note the spacial dimensions of this sonnet. It begins, as Keats often does, with a vertical reference point: up there, in the heavens. Our mind’s eye is already tilted upwards. In his early sonnet, To One Who Has Been Long in City Pent (1816), he opens with a similar image, looking up ‘into the fair and open face of heaven’ (line 2); and again in On the Grasshopper and Cricket (1816), the ‘hot sun’, and the birds nestled in the ‘cooling trees’ above are the first objects of his gaze. Throughout these sonnets, there is a gradual lowering of sight, down into the realm of sense and feeling as the lines progress. In this case, Keats begins high up among those sleepless stars, the realm of ‘steadfast’ ideals. Part of the main problem the poet seeks to address is his struggling to identify with this star. It is lofty—dizzyingly so—and we may become disoriented if we tilt our necks upward for too long. Keats wishes for identification (would I were as thou art), but in the next lines he immediately explains the type of identification he is after:

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night And watching, with eternal lids apart, Like nature's patient, sleepless Eremite,

To be bright and intense, yes, but not to be alone and unreachable . To be steadfast and still, but not to be always engaged and occupied, patient and changeless. Not to be like Nature’s version of an Eremite (a hermit or recluse), always looking down upon, and never feeling, the earth’s skin and touch:

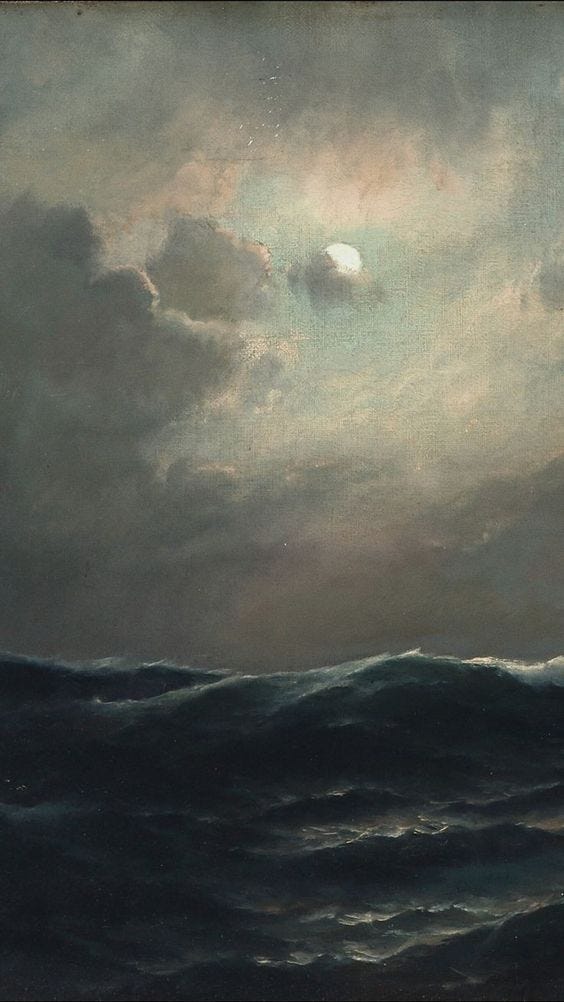

The moving waters at their priestlike task Of pure ablution round earth's human shores, Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

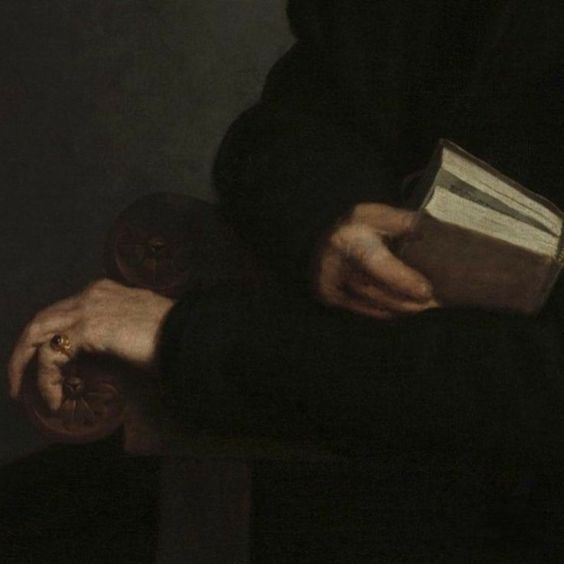

After explaining that it is not the bodiless sublimity of the Star that he is after, Keats brings his gaze back down to earth, expressing his love for the world’s tactility, the desires of the body and the goodness of sensory experience. Indeed, the earth has its own holiness. Its ‘moving waters’ are ‘priestlike’, and perform a type of ‘ablution’ (a purifying or cleansing) along the shores of the world. Though some part of the poet longs for that perfect, bright ideal of the divine which the star represents, he admits he could not be removed from the snow, moors or mountains. Moving still deeper into the vale of touch and sense, Keats moves in the volta of the sonnet (a Volta being the shift, or turn in tone which usually happens in the ninth line of a Petrarchan sonnet) to that ultimate form of human sense: the closeness of sexual experience shared between two lovers:

No—yet still steadfast, still unchangeable, Pillow'd upon my fair love's ripening breast, To feel forever its soft fall and swell, Awake forever in a sweet unrest,

Beginning in the disembodied ether, the sonnet now ends in the throes of sheer embodiment, the complete sharing of one’s body with another. In Wordsworth’s The Excursion, quoted above, the lofty and unreachable nature of the Star is part of its appeal—its very inhumanity only serving to highlight its desirability. Keats reworks this cold and distant star into the warm, intimate embrace of Bright Star’s sestet. Keats does not want those otherworldly, sublime qualities of the star of Wordsworth—no, he says—he wants the never-ending closeness of two lights come together in mutual self-giving; an eternal embrace between himself and his lover:

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath, And so live ever—or else swoon to death.

In view of the whole sonnet, it seems that Keats is actively weaving in the natural imagery of the octave (first eight lines) with the human and personal imagery of the sestet (last six lines). The constancy of the ‘Bright star’ is also the eternity of the lover’s union, so ecstatic in feeling it is wished to endure, even ‘to death’. The ‘moving waters’ of the shore are also the ‘soft fall and swell’ of his lover’s breast; and the ‘soft-fallen’ snow resting upon the mountain side is also the poet’s cheek, ‘pillowed upon’ his fair love.

One of the things I tend to realise after analysing a poem through a close reading, is that there are so many new links and interpretive possibilities which open before us. This kind of line-by-line analysis, I have found, rather than diminishing a poem by limiting its possible meaning, allows us to move into a new space of reading. We have reduced the distance between us and the poem (and in some sense, the poet). This initial clearing away of the fog of obscurity is necessary, I think, to move into spheres of greater closeness, helping the lines hover about in our memories like an old friend.

Works cited:

- Gittings, Robert. John Keats (biography). London: Penguin Books, 1968.

- Gittings, Robert. Letters of John Keats. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

This is absolutely wonderful!

"...after analysing a poem through a close reading, is that there are so many new links and interpretive possibilities which open before us..." can't agree more with this! I am finding Keats's work more and more beautiful (and Hölderlin's too)

Very enjoyable, thank you. I will have to send A. Christine Myers your way. She writes good stuff. https://substack.com/@smallsunnygarden