With the severity of a judge delivering a sentence, in the final lines Donne passes down his verdict: ‘death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.’ As with the pounding of the gavel, there is a distinct severity and finality of tone. The speaker has seen past the veil and found nothing to fear. He is now free.

Hello all. Here is a short, line-by-line commentary of John Donne’s classic poem, Death Be Not Proud. Paid subscribers will be able to read the entirety of the commentary. I really am so grateful for your support. Mentioned below is also a brief description of the writer himself, and of the poetic form (the sonnet) that he had mastered. I hope you enjoy!

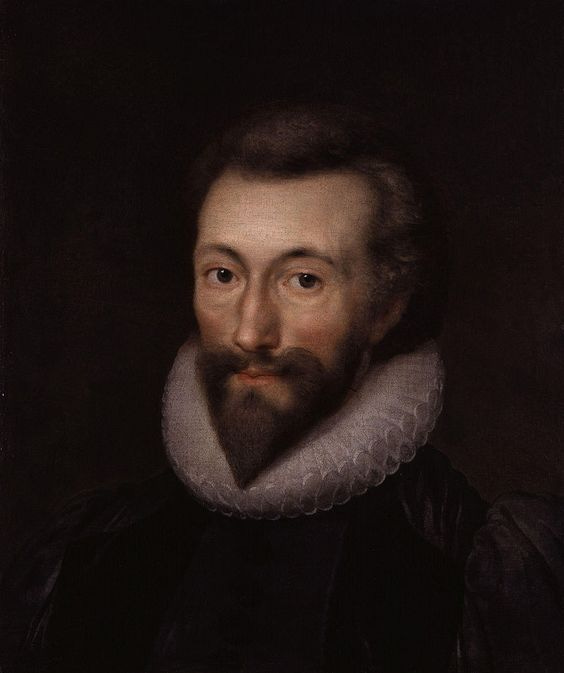

John Donne

John Donne (1572-1631) was an English writer and Anglican cleric who wrote primarily during the Jacobean era, and is best known for his devotional and spiritual use of the sonnet form. He accomplished this most notably in his corpus of Divine Poems, the Holy Sonnets. Of the nineteen sonnet’s within this collection, I will be focusing on Donne’s most existential work, Death Be Not Proud, written in 1609 whilst he suffered a major, life-threatening illness.

What is a Sonnet?

Originally derived from the Sicilian word, sonetto, which means ‘little song’, what we know as the ‘sonnet’ today—a fourteen line poem with a strict rhyme scheme and specific structure—was solidified by the thirteenth century. Donne’s Holy Sonnet, Death Be Not Proud, is a ‘Shakespearean sonnet’, as the particular form it adheres to was first popularised by the English poet and playwright, William Shakespeare. Its structure consists of three quatrains and a couplet, adhering to the metrical technique of iambic pentameter. However, while Donne’s poem generally adheres to the structure of a Shakespearean sonnet, it follows the rhyme scheme (albeit with slight variation) of an Italian sonnet—that is, abba, abba, cddc , ae.

The Poem

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die. Analysis

The speaker begins by addressing Death as a person—as subject—in a powerful act of personification:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

Throughout this sonnet, the literary technique of apostrophe, which occurs when a writer is addressing a subject who cannot, or will not, respond, is used in order to establish a judge-vs-criminal dynamic between the speaker and Death. Indeed, Death, as he listens to these accusations, is mute. From these opening lines we can grasp that Donne seeks to reassess and deconstruct the role of Death, and we have been invited to watch on from the stands as the verdict is carried out.

For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. Donne refers to the accused as ‘poor Death’, intimating the degree to which he feels superior—himself being assured, as a baptised Christian, of his inheritance in God’s kingdom, in that ‘new heaven and new earth…where righteousness dwells’, as the second epistle of St. Peter describes (2 Pt. 3:12-13). Death is here presented as being powerless to do the very thing for which he is universally feared: to kill, to end life and snuff out the light of the soul. Thus ends the first quatrain of Donne’s Holy Sonnet.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

Here, ‘rest and sleep’ are described as ‘pictures’ of Death—brief anticipations of a reality yet to be fully realised. What is this ultimate rest, this most pleasurable of all states? The answer, the speaker is coming to realise, is Death itself. If rest and sleep are but pictures of Death, and those things are pleasant, then from Death can only come more pleasantries. Donne is here attempting to deprive Death of its terrifying connotations, divesting that ancient threat of all dread and terror.

There a similar picture of Death within the work of one of Donne’s contemporaries, William Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet (1601), written eight years prior to Death be Not Proud, in its most enduring soliloquy represents Death as a kind of sleep:

[…] To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to; ‘tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished.

(Act III Scene I)

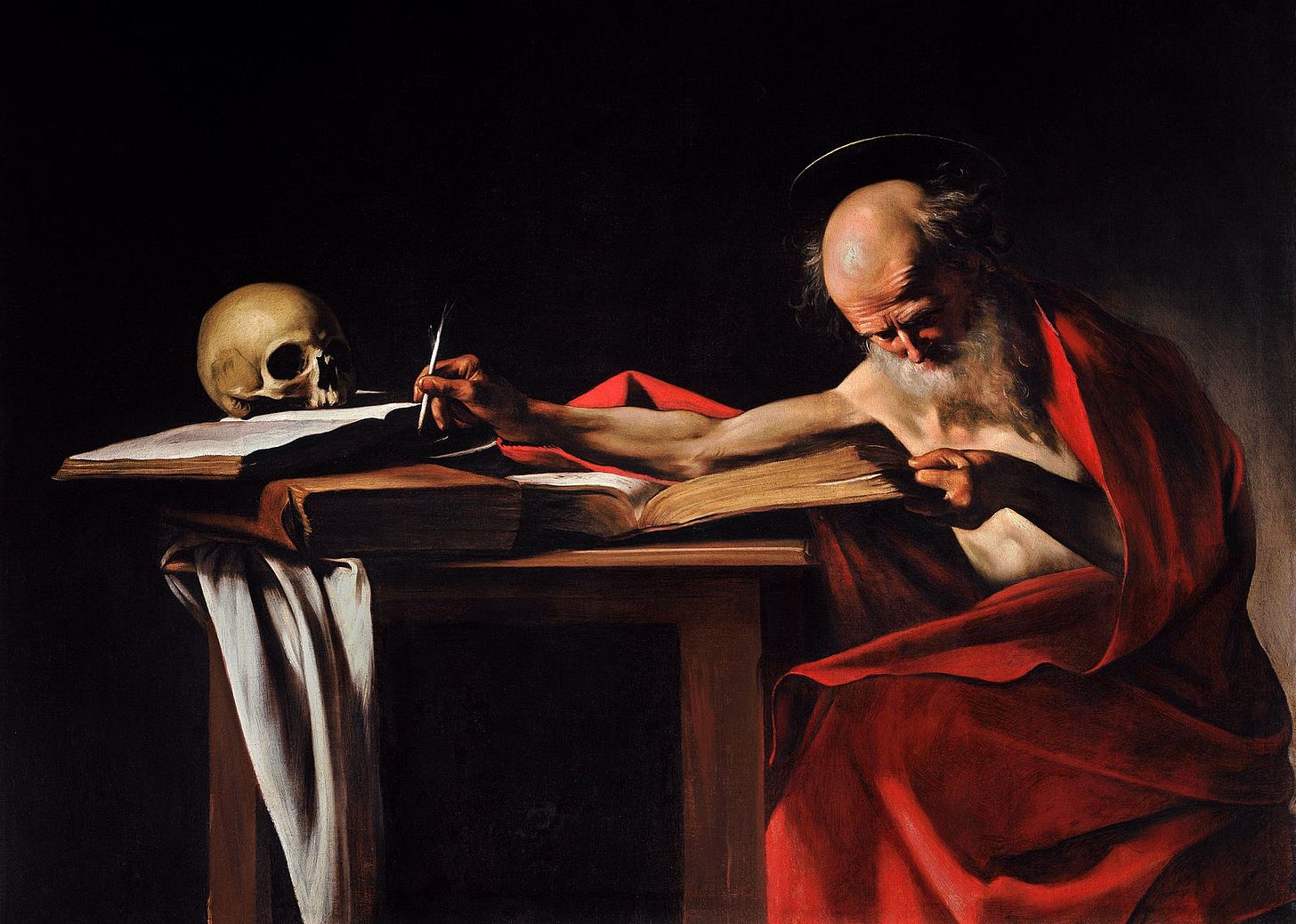

And in the epistles of the New Testament (which, as an Anglican cleric, Donne would have been intimately familiar with), there are numerous times where ‘brothers and sisters’ of the Faith who have died, are said to have ‘fallen asleep’ in hope of the resurrection (I Cor. 15:6).

And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery.

The speaker provides an explanation for the old adage, ‘Only the good die young’, suggesting that the ‘best men’ are called to die in youth because God wants them to experience the bliss of that eternal rest sooner rather than later. It is a ‘Rest of their bones’, and a ‘delivery’, for their souls to be taken from what Hamlet describes, in the aforementioned soliloquy, as ‘[the] grunt and sweat [of] a weary life’.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

Coming to the volta, or turn of the poem (that part of the sonnet’s structure, usually occurring around line 9, in which there is either a shift in the speaker’s argument, or a significant development upon it) we see that the speaker has assumed a far more aggressive mode of accusation. Whereas before, Donne almost seemed to pity Death in its powerlessness, wishing only to remind it of its role as a mere instrument of nature, or of the divine will, he now skilfully employs the rule of three, declaring Death to be a slave to ‘Fate, Chance, [and] Kings’; a slave that dwells with ‘poison, war, and sickness’. At this point in the sonnet, we should note that Donne has moved away from representing Death as a mere mediator between a wearisome life and blissful rest, and has instead adopted a significantly harsher rhetorical mode of address. He has now declared that the dwelling space of Death—and therefore it’s very nature, by association—is a kind of depraved sty filled with the most undesirable qualities of human life.

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then? Two unbroken lines of iambic pentameter, indicating some sense of ease after the sudden burst of accusation in the previous two lines. However, the speaker nevertheless ridicules his subject, claiming that even drugs can induce as restful a sleep—and ‘better’—as anything Death could himself achieve. So, asks the speaker, ‘why swell’st thou?’ Death has nothing to be proud of, no charge which is distinguished or exclusive to himself.

One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

In keeping within the interpretative frame of a courtroom scene, this final pronouncement—the ending couplet of the sonnet—delivers what is essentially a sentence of capital punishment upon the accused. In the previous three quatrains Donne had been building a case and mounting evidence, until he had thoroughly deconstructed his subject and was compelled to pass his final verdict: the death of Death. With the severity of a judge delivering a sentence, in these final lines Donne passes down his verdict: ‘death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.’ As with the pounding of the gavel, there is a distinct severity and finality of tone. The speaker has seen past the veil and found nothing to fear. He is now free. Assured of his place in heaven, Donne therefore thinks it no great thing to have but ‘One short sleep’ before ‘[waking] eternally’ and coming into his Heavenly Father’s kingdom. Here, Donne is alluding to the traditional Christian doctrine of the Resurrection of the Body, wherein the souls that are asleep—i.e., those that have died before the second coming of Christ—are brought back from the dead. At such a time, Donne argues in the final couplet, the need for Death as mediator between life and death has diminished—his function is no longer necessary. Donne derives the inspiration for these lines, of course, from the New Testament, where St. Paul writes, in a letter to the Corinthian Church in Greece, that when Christ returns, “The last enemy that will be destroyed is death” (1 Cor. 15:26). Furthermore, in the Apocalypse of St. John, there is a similar image of the coming Kingdom of Heaven:

[…] God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away.

(Rev. 21:4). The Power of the Sonnet

Far from acting as a restricting force, warring against a poet’s freedom and imagination, the sonnet form (though perhaps a little out of style in today’s poetry scene), in its limitation, allows for an argument to be fine tuned; for lines to be concise, crafted and effectual in its delivery; to leave the reader with a single and lasting feeling. After all, a Sicilian little song, in the hands of a skilled writer, is capable of deconstructing even Death itself.

Wow, what a powerful analysis. I've been trying to read more sonnets and I'm so thankful I came across this post. I love how you explore the poem through the lens of a courtroom trial, this somehow made me love the poem even more. Thank you for this

Bravo for bringing that beauty back and resuscitating it for us all.