‘The woods are lovely, dark and deep’, because they promise a profound and abiding rest for the weary traveller, and a lasting respite from worldly affairs and responsibilities. Frost reminds us that our promises—those commitments that we have made either to ourselves or to others—are cause enough to walk through the dark night and on into safe lodging.

Hello all, I have recently been going over some of Robert Frost’s poetry, and thought I would share some of my thoughts. Robert Frost (1874-1963) was an American poet known particularly for his descriptions of rural life and experience. Harold Bloom has described him as ‘a subtle master’, and ‘far more difficult than he appears to be’ at first glance (Bloom, 817). Frost was a modernist who wrote in unadorned, plain language, a style which helped foster an enormous popularity in his later career, not only among the literary intelligentsia of Britain and America, but also among uneducated, everyday people, who valued his natural and unaffected style. A landmark moment in his career would come in January of 1961, when he was asked to recite a poem for the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, who was himself a great lover and patron of arts and poetry. In more recent memory, I was surprised to find that George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series was inspired by Frost’s short poem, Fire and Ice (1920).

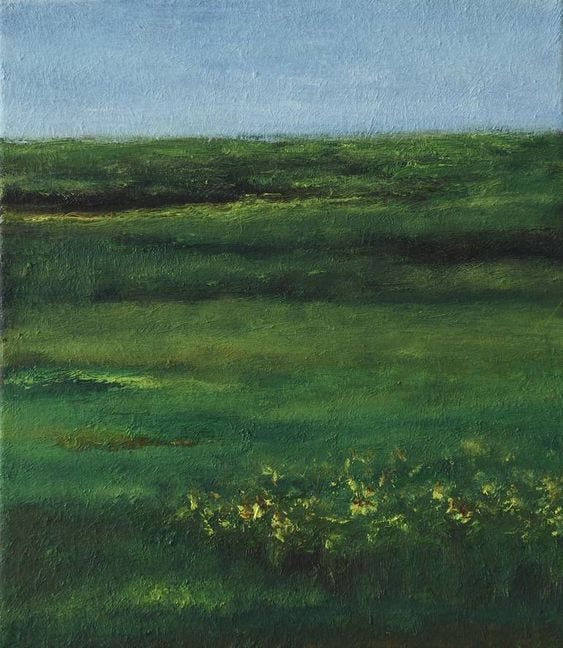

This relatively early poem of Frost’s, My November Guest (1913), is an ideal example of his ability to, in the words of historian, Ken Mondschein, capture the feel ‘of quiet rural places’ (Mondschein, xiv):

My sorrow, when she’s here with me,

Thinks these dark days of autumn rain

Are beautiful as days can be;

She loves the bare, the withered tree;

She walks the sodden pasture lane.

Her pleasure will not let me stay.

She talks and I am fain to list:

She’s glad the birds are gone away,

She’s glad her simple worsted grey

Is silver now with clinging mist.

The desolate, deserted trees,

The faded earth, the heavy sky,

The beauties she so truly sees,

She thinks I have no eye for these,

And vexes me for reason why.

Not yesterday I learned to know

The love of bare November days

Before the coming of the snow,

But it were vain to tell her so,

And they are better for her praise.A sorrow, continually felt, like the dark days of autumn rain. In Frost’s poetry, I have noticed a kind of subjective landscape projection, where the poet’s inner world of mind and heart colours the outer world of trees and pastures. And although this inner-colouring is often grey and sorrowful, as in My November Guest, those days of darkened contemplation are still ‘as beautiful as days can be.’ In this melding of the intrapersonal and environmental, of the realm of psyche and the realm of Gaia, depression seems to take on a poetic and redemptive quality, one that makes the world more beautiful, even amidst its fallenness. The ‘desolate, deserted trees […] The faded earth, the heavy sky’ are all ‘beauties’ that his sorrow ‘so truly sees’. It is towards this poetic seeing, the art of finding beauty and redemption in the most tragic of human states, that all poets and writers should aspire. In the end, as Frost writes in the final line, there is a special beauty and lustre in poetic sorrow, and the darkness of those days ‘are better for her praise’.

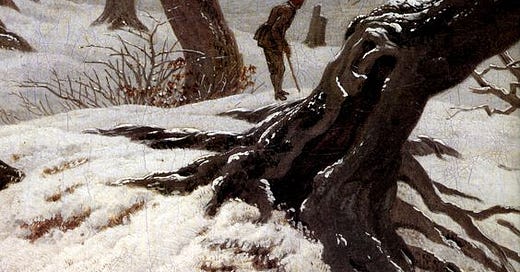

In the opening lines of An Old Man’s Winter Night (1916), Frost writes again of a familiar darkness, but shies away from welcoming it as he once did, and instead moves towards the warmth of a solitary light:

All out of doors looked darkly in at him Through the thin frost, almost in separate stars, That gathers on the pane in empty rooms. What kept his eyes from giving back the gaze Was the lamp tilted near them in his hand.

In the subject’s hand is held a glowing lamp. When held aloft, this light

[...] scared the outer night, Which has its sounds, familiar, like the roar Of trees and crack of branches,

Although at times Frost clearly embraced the darkness and the cold, and the psychological states they represent, here he is holding a light against Winter herself, guarding against an environment that has apparently turned against him. This light, which may symbolise his creative spirit, aids in some small way in warding away a cold and isolated interiority. But this inner light cannot dispel the loneliness which follows the old man, the poem’s subject, wherever he goes. In the end, ‘A light he was to no one but himself […] A quiet light, and then not even that.’

So often in Frost’s poetry, there is a kind of subtlety that overwhelms, and a softness that lands heavily on the senses. Consider this next poem, Dust of Snow (1923), and the way in which its quietness resounds in a powerful way:

The way a crow Shook down on me The dust of snow From a hemlock tree Has given my heart A change of mood And saved some part Of a day I had rued.

The quiet rustling of snow-laden branches, the twitch and shuffle of crow’s feet, all amounts to a shift in consciousness for the subject: ‘A change of mood’ which ‘saved’ the rest of his day. The lasting sensory impact left by these quiet images calls to mind James Wright’s free-verse poem, A Blessing (1963), where the image—nature—itself is enough:

Just off the highway to Rochester, Minnesota, Twilight bounds softly forth on the grass. And the eyes of those two Indian ponies Darken with kindness. They have come gladly out of the willows To welcome my friend and me. [...] They begin munching the young tufts of spring in the darkness. I would like to hold the slenderer one in my arms, For she has walked over to me And nuzzled my left hand.

In the climactic line, Wright’s consciousness (which has been fed, poetically, almost to a point of overflow by these images) cannot help but pour out of itself, expanding into a greater sphere of experience: ‘Suddenly I realize / That if I stepped out of my body I would break / Into blossom.’

Similarly, subtle shuffles and quiet sounds are prominent in what is perhaps Frost’s most widely loved poem, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening (1922):

Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year. He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound’s the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake. The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep.

When I imagine this man, alone with only his consciousness and a horse for company, watching on as the woods ‘fill up with snow’, there is an overwhelming sense of tiredness and sorrow which comes through. Like much of Frost’s poetry, the setting is cold and dark—‘The darkest evening of the year’—and yet this darkness takes on a familiar and comforting quality, much as the ‘dark days of autumn rain’ inspired contemplation and solace in his earlier work, My November Guest. ‘The woods are lovely, dark and deep’, because they promise a profound and abiding rest for the weary traveller, a lasting respite from worldly affairs and responsibilities. For many of us, I am sure we have felt this influence at times, even if only from the borders of our consciousness. Yet there are times when these woods are all around us. Frost reminds us that our promises—those commitments that we have made either to ourselves or to others—are cause enough to walk through the dark night and on into safe lodging. I have found that it is also at these times that our capacity for poetic seeing and creative thought is most alive and dynamic, when we are alert to the small voices which beckon our pen this way or that. Frost reminds us that beautiful, profound and creative thoughts often come from sorrow and have their home there. Perhaps, if we learn to see poetically, we can become more attentive to those moments of grace which shine through even amidst the dark woods of the world.

Works cited:

Bloom, Harold. The Best Poems of the English Language: From Chaucer Through Robert Frost. New York: HarperCollins, 2004.

Mondschein, Ken. A Collection of Poems by Robert Frost. Introduction. San Diego: Canterbury Classics, 2019.

Wonderfully analyzed . Inspiring.

I think "Fire and Ice" is one of the most perfect poems in the English language. Your intuition about "Stopping by the Woods..." is really intriguing. There is a call to a more inclusive, ecstatic consciousness, and the pull back to quotidian life. I never saw that before. Thanks.