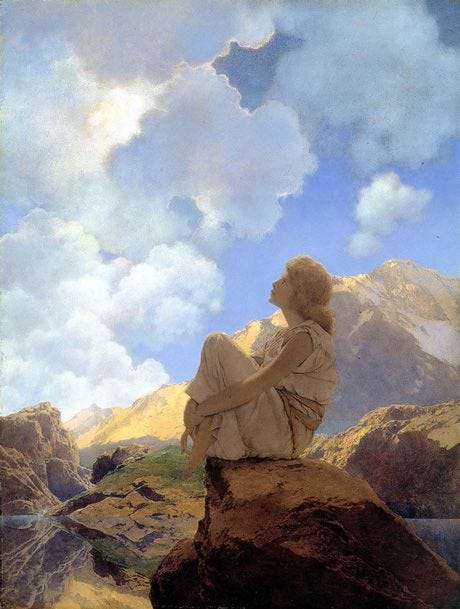

She is moved beyond the uncertainty of choice and limitation, which the Fork and Forest of ‘Our Journey Had Advanced’ perhaps represent. Now, she is swept up into the realm of higher things. Imminence: an unalterable, shimmering light now drags her soul—a soul changing, even now—into the centre of the circle, towards that Primeval Presence which first invaded her at birth and sustains her creative work even until now.

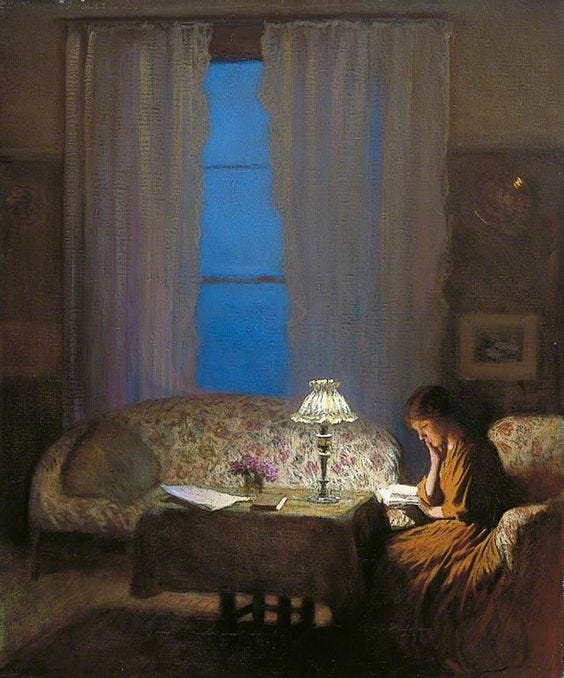

Over these past few months I have been reading through the poetry of Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), a poet whom literary critic, Harold Bloom, has named among ‘the two greatest and most original of American poets’, alongside Walt Whitman (Bloom, 574). ‘At her strongest’, he continues, her work ‘is so cognitively original’ that she challenges even the personal mythologising of William Blake, and even ‘has something in her lyrics that recalls the swiftness and compression of Shakespeare’s mind’ (Bloom, 575).

Such poetic gift as Emily possessed, however, was closely guarded. Amazingly, throughout her lifetime she rejected publication for the vast majority of her poetry, choosing instead to keep them for herself, or enclose them in letters to friends. As far as style is concerned, Bloom confidently places her as ‘a High Romantic poet, influenced by Emerson and Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats’ (Bloom, 577).

In this letter I will share some thoughts on two of her poems which I have found especially moving. Often, I find her lines floating around my mind while going about my day. Consider this profound text, This Consciousness That is Aware:

This Consciousness that is aware Of Neighbors and the Sun Will be the one aware of Death And that itself alone Is traversing the interval Experience between And most profound experiment Appointed unto Men— How adequate unto itself Its properties shall be Itself unto itself and none Shall make discovery. Adventure most unto itself The Soul condemned to be— Attended by a single Hound Its own identity.

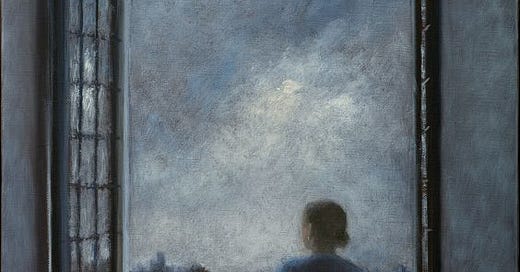

This consciousness that is aware / Of Neighbours and the Sun. Incredibly, in these first two lines, Dickinson sweeps across the whole vista of human experience. Awareness (inner life), neighbours (human society, civilisation), and the sun (Nature in its entirety), enclose all there is for us humans to see and experience. This easiness of composition must be what Bloom intends to mean when he writes, ‘She makes the whole universe her playpen’ (Bloom, 578). Only rarely leaving her father’s farm in Massachusetts, she lived an isolated life. And yet, one quickly learns that she does not need to go out into the world to glean insight and inspiration. Through an innate power, she brings the world to herself.

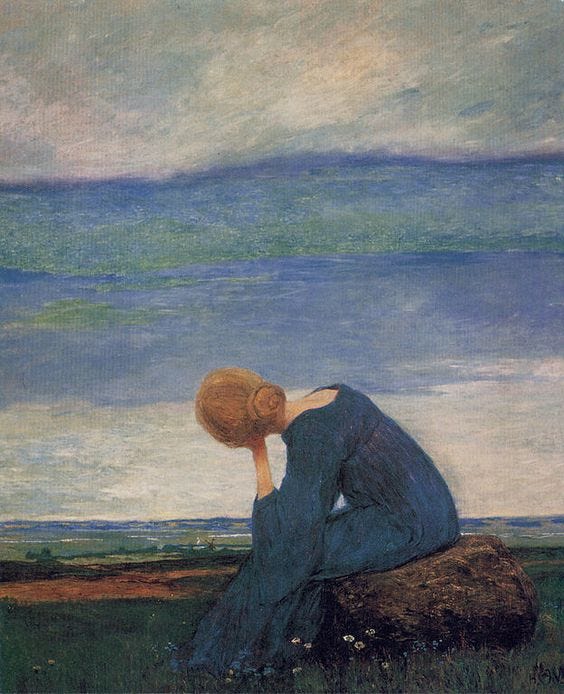

Not content to rely only upon the seen realm, she often grasps for hidden things. In this poem, she explores ‘the interval / Experience between’ birth and death; appreciating, too, wide-eyed and questioning, this ‘most profound experiment / Appointed unto Men’ — the duration of a soul, its contact with other selves, its relation to nature and its closeness to every thing. Though raised in Calvinism (a quite austere version of protestant Christianity), ‘Emersonian self-reliance is her fundamental principle, and hers is a private religion of the self’ (Bloom, 575). This self reliance shines through as she writes about consciousness: that mysterious, self-referential human property: ‘How adequate unto itself […] Itself unto itself’.

Terrifyingly, in the final lines, Emily ponders the possibility that this self, by far the most powerful part of a human being, may survive in Death— ‘The Soul condemned to be’. This startling thought, according to literary critic, David R. Williams, that after death there remains only a ‘consciousness of endless consciousness’; that our shuffling off of the flesh may leave one ‘alone, without body, without perception, forever and forever, fully awake’, must have terrified her. And yet, throughout her poetry she remained ‘infinitely transfixed by the abyss at the centre’ of things (Williams, 360). Often, according to Robert Gillespie, writing in the New England Quarterly, her poems begin in the small and familiar, yet inevitably ‘progress outward, upward, away, into the large and vast, eternity and immortality.’ (Gillespie, 250). It is this ‘special vocabulary of awe’ (Gillespie, 250) that is especially on display in this next poem, Our Journey Had Advanced:

Our journey had advanced— Our feet were almost come To that odd Fork in Being's Road— Eternity—by Term— Our pace took sudden awe— Our feet—reluctant—led— Before—were Cities—but Between— The Forest of the Dead— Retreat—was out of Hope— Behind—a Sealed Route— Eternity's White Flag—Before— And God—at every Gate—

There is a real sense in which she is feeling around for the outer edge of things. While most of us, I would say, may be content, whether out of comfort or fear, to stay within the centre, she does not shy away from the arcane or mysterious. Indeed, a principle of discovery animates her work.

In the above lines, ‘that odd fork in Being’s Road—/Eternity’, clips her spirit with ‘sudden awe’, and she is led to ‘Cities’. This rapturous imagery calls to mind the descent of the New Jerusalem in the 21st chapter of St. John’s Apocalypse. The splendour of white walls, high and fantastical, does not produce a rosy sentimentality, however. Even on that road, there is still ‘that odd Fork’, uneven and questioned, flanked by ‘The Forest of the Dead’. I wish I knew what this forest entailed, but so much of Emily’s work is shrouded in a veil and is difficult to decipher. However, before I, and perhaps even she, can guess, the poet is moved beyond the uncertainty of choice and limitation, which the Fork and Forest perhaps represent. Now, she is swept up in the realm of higher things. Imminence: an unalterable, shimmering light now drags her soul—a soul changing, even now—into the centre of the circle, towards that Primeval Presence which first invaded her at birth. The predestination of Calvin surfaces for a moment: ‘Retreat—was out of Hope […] Behind—a sealed Route—’; finally, the choice has been made for her. In a gesture, perhaps symbolising a kind of surrender, she sights ‘Eternity’s White Flag’, and in a terrifying brilliance, at once inescapable and irresistible— ‘God—at every Gate.’

Works cited:

Bloom, Harold. The Best Poems of the English Language. New York: Harper Collins. 2004.

Gillespie, Robert. “A Circumference of Emily Dickinson.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 2, 1973, pp. 250–71. JSTOR.

WILLIAMS, DAVID R. “‘THIS CONSCIOUSNESS THAT IS AWARE’: Emily Dickinson in the Wilderness of the Mind.” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 66, no. 3, 1983, pp. 360–81. JSTOR.

Loved this piece. I think sometimes feeling around in the outer edge, intimations, is where we should seek to linger. Seems to me that Dickinson feels like a ladder, even when (or maybe especially) shrouded in a veil and difficult to decipher..

Bloom seems to encapsulate her completely in his descriptions: ‘so cognitively original’; ‘She makes the whole universe her playpen’; ‘hers is a private religion of the self.' Beautifully written❤️