‘You must recollect that Psyche was not embodied as a goddess before the time of Apulieus the Platonist [Numidian philosopher (124-170 C.E.] … and consequently the Goddess was never worshipped or sacrificed to with any of the ancient fervour—and perhaps never thought of in the old religion—I am more orthodox than to let a heathen Goddess be so neglected.’

In this letter to George and Georgiana Keats (February – May, 1819), John Keats goes on to write that ‘Ode to Psyche’ was, of his then most recent writings, ‘the only one with which I have taken even moderate pains’, and that he thought ‘it reads the more richly for it.’ These pains are certainly reflected in the text. It is charged with a high sense of spirituality, recalling that golden era of classical paganism which the Romantics so admired.

Indeed, a kind of wistful pagan magic reverberates throughout the stanzas.To begin, the poet calls upon—through invocation—the beautiful and mysterious Psyche—“O Goddess!…O brightest!” Psyche, for the Greeks, meant something like “soul”; and in our parlance, has come to mean psychology, inner life, or the mental/spiritual reality of our being. Let us not think, however, as Dr. Malcom Guite warns against, that “Psyche” can be reduced merely to the realm of biological stimuli, the brain, as some today may believe. Psyche is something more, something deeper in us that cannot be named, and perhaps can only be adequately explored through such means as myth and song, as Keats is undertaking here. Psyche was the most beautiful and praiseworthy of the gods, thought Keats, perhaps because she represents the core of the creative being: the wellspring from which the poetic imagination is sourced.

Simply stated, as Robert Gittings writes in his biography of the poet, ‘As a poem of ideas, [Ode to Psyche] sticks to its brief of simply stating that Keats will be the poet-priest of this hitherto hardly-recognised deity, the soul.’ This soul, he goes on, represents for Keats ‘a perfected spark of God.’

A common theme in Keats’ poetry is the question of what constitutes illusion, and what reality. In ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, written only a month after ‘Ode to Psyche’, he asks, in the final lines, “do I wake or sleep?” And in his famous poem, “On Death”, he asks, “can death be sleep when life is but a dream?” Similarly, in the first Stanza of this Ode, he writes in a tone of wonder, recalling the array of feelings which charged through him as he wandered through enchanted woods: “Surely I dreamt today, or did I see / The winged Psyche with awaken’d eyes?” For Keats, the imaginative and illusory often bleeds into the real world of ‘things’, and allows for a feeling that this world is being renewed and re-enchanted.

J.R.R. Tolkien, himself belonging to the Romantic tradition, writes in ‘On Fairy-Stories’, that the realm of fantasy (or, in this context, of poetry) constitutes a “recovery” of what is most real. Great literature is a flight to reality, not away from it. It is the real stuff, not mere illusion. In this “recovery”, Tolkien writes, we can experience a “re-gaining—re-gaining of a clear view”. Echoing this, Dr. Malcom Guite, in an address on Coleridge, remarked that poetry can help us see reality as it really is, in all its excitement, mystery, and sublimity, piercing through what Coleridge called the “film of familiarity”, or what Tolkien named that “drab blur of triteness”—this same veil that the poet of this Ode indeed suspects that he has peeked behind, if only for a few moments.

Many of the Romantic poets felt this same yearning for re-enchantment. William Wordsworth famously lamented, in his sonnet, “The World is Too Much With Us”, that “I’d rather be a pagan, suckled in a creed outworn / So might I, standing on this pleasant lea / Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn.” Keats expressed this same frustration with his world, the world of machines and logic and overbearing reason. But for him, although there is “no lute…no pipe”, and no “sincere” belief at all amongst humanity for those lost realms of Arcadia, those “fallen Olympian gods”, he is nevertheless stedfast and firm: “I will be thy priest”. He will, through the power of his poetic imagination, “build a fane” [a temple], and “a rosy sanctuary” for Psyche to dwell in. In a wonderful example of sibilance, Keats will sway the “chain-swung censer”, and fill his mind with the “sweet incense” worthy of a goddess.

Like in his wonderful ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, written only a month later, the “viewless wings of Poesy” allows him to explore these realms that are otherwise inaccessible. Lost, now, are those “happy pieties” which instilled the awe and wonder that Keats so apparently missed. “Holy” was air, fire, water—the structural elements of the universe. To say that nature is—or was—holy, is to say that it is set apart, distinct, and alive in itself, and therefore valuable in itself.

What is the answer to this encroaching mechanisation that the poet seeks to guard against, this oncoming world which seeks to reduce all colour and beauty to a uniform, uninspired grey?

I think that we can say, along with Keats and the other Romantics, that the poetic imagination, which can indeed aid us in the endeavour of our lives, which allows us to see ourselves and others in new and fresh ways—indeed, with the Romantics, we can say that the soul of humanity—our Psyche—is what is most special in us, and what should be cultivated above all else. It alone can combat the oncoming blur of mediocrity that lingers around our lives, the searching grey which seeks out weakness in our foundation. The cultivation of that deep and mysterious part of us, which we recognise looking back at us, as in a clear mirror, in the great literature of the world, can safeguard our souls from that fast-approaching horizon of unfulfilled potential that threatens every one of us.

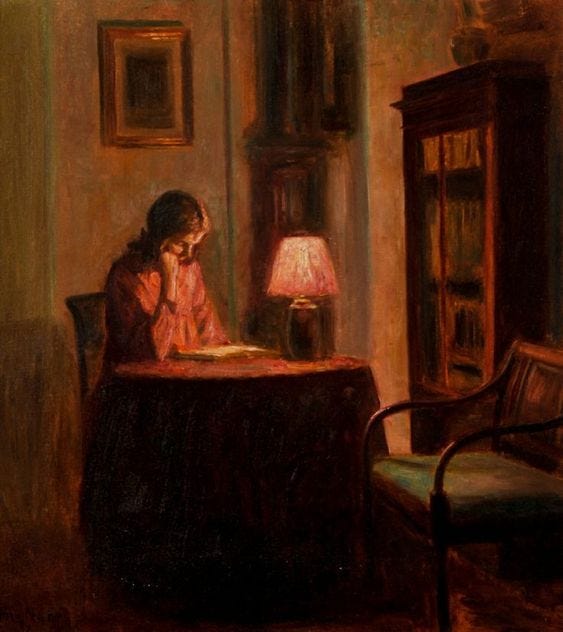

Each of us, then, considering the concluding stanza, can build our own sanctuary within that “shadowy” realm of thought, such that peace and natural feelings shall reign “and murmur in the wind”. Each of us, with Keats, can in that innermost sanctum light the bright torch, igniting our world with the fire of wonder and enchantment:

And in the midst of this wide quietness

A rosy sanctuary will I dress

With the wreath'd trellis of a working brain,

With buds, and bells, and stars without a name,

With all the gardener Fancy e'er could feign,

Who breeding flowers, will never breed the same:

And there shall be for thee all soft delight

That shadowy thought can win,

A bright torch, and a casement ope at night,

To let the warm Love in!

Works cited:

- Gittings, Robert. Letters of John Keats. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Kreeft, Peter. The Philosophy of Tolkien. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005.

- Guite, Malcom. Keats’s Ode to Psyche.

- Guite, Malcom. Mariner: Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Voyage of Faith.

I found out recently that there is a type of butterfly called Psyche, as well as a genus of moth, which I thought wonderfully beautiful! I think it's perhaps to do with the fact that the Goddess is often depicted with butterfly wings...