As Clarke noted, ‘certain passages in The Iliad had such a stirring effect upon Keats that “he sometimes shouted”’ (Gittings, 130). In the following week, Clarke described Keats’s sense of excitement and anticipation for the possibility of a life of pursuing literature and poetry full-time.

John Keats’s sonnet, On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer, was written on the weekend of the 11th and 12th of October, 1816. At this time, he was only 21 years old. It is one of the most important poems in Keats’s body of work, and it is often anthologised due to its providing a window into the context of early nineteenth century views of classical literature. According to scholar and literary critic, Robert Gittings, ‘It is the first poem by Keats to have [a] fully free movement of original creation […] whole in conception and imagery’ (Gittings, 129). The poem is written in the Petrarchan sonnet form, with an octave (first eight lines), a Volta (the turn or shift in argument which occurs in line nine), and a sestet (final six lines). It details his experience of having been exposed, for the first time, to certain passages of George Chapman’s English translation of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold , And many goodly states and kingdoms seen; Round many western islands have I been Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

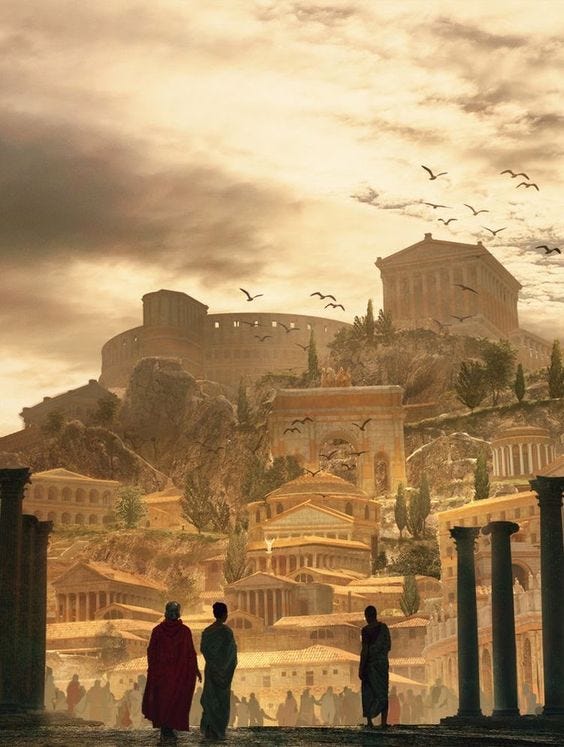

Those ‘realms of gold’ in which there are ‘goodly states and kingdoms,’ refer to the texts of classical literature, those ‘western islands’ of pagan antiquity (primarily Greece). Keats had read much in this area, and in his own way seems to have been enchanted by these vistas. Apollo, among other things, was the god of music, poetry, prophecy, light and youth, and Keats apparently held ‘a deep-seated belief in the [god’s] inspiration’ (Gittings, 131).

It is notable that Keats, throughout this sonnet, utilises a travelling metaphor. This metaphor is sustained, and illustrates a vivid sense of the imaginative involvement and closeness he has with these ancient texts. He has not merely read and thereby imagined himself in their narrative settings—he has, in some sense, really ‘travelled’ there, and ‘seen’. This is not a literal, spacial seeing, but a poetic seeing, a clear picture in the mind’s eye accompanied by what Coleridge called, in his poem, This Lime Tree Bower my Prison (1797), a ‘swimming sense’. Already in the first half of this octave we see the capacity of the poetic imagination, and may relate to this way of seeing ourselves. The tidy rhyme scheme, too, combined with the consonance of the ‘L’ sounds, communicates this imaginative power through a flowing lyricality.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told That deep-brow'd Homer ruled as his demesne; Yet never did I breathe its pure serene Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Often, Keats had been told of the literary wealth of the deep-brow’d (meaning one of great intellectual power) Homeric texts, The Iliad and The Odyssey. But it was not until the night of the 11th or 12th of October, as he was staying overnight at a friend’s house (Charles Cowden Clarke), that he witnessed the reading aloud of certain selected passages of Chapman’s translations. Keats wrote the entirety of the sonnet (allowing for a few later revisions) the morning after this encounter with Homer by the fireplace. As Clarke noted, ‘certain passages in The Iliad had such a stirring effect upon Keats that “he sometimes shouted”’ (Gittings, 130). In the following week, Clarke described Keats’s sense of excitement and anticipation for the possibility of a life of pursuing literature and poetry full-time:

The character and expression of Keats's features would arrest even the casual passenger in the street; and now they were wrought to a tone of animation that I could not but watch with interest...As we approached the Heath, there was the rising and accelerated step, with the gradual subsidence of all talk. (Quoted by Gittings, 131).Soon afterwards, Keats would make the decision to leave the medical profession, where he was training to be a surgeon. To quote from a later letter of Keats, it seemed from that night by the fireplace, as he listened to Chapman’s text, through Clarke, spoken out ‘loud and bold’, that ‘the creature had a purpose and its eyes [were] bright with it’ (Letter to the George Keats’s, 14th February - 3rd of May, 1819).

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken; Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men Look'd at each other with a wild surmise— Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

The volta, or turn of the sonnet, begins in the sestet. Then felt I like some watcher of the skies. The line not only builds upon the theme of discovery which had been steadily rising in the octave, but seems to introduce a new sense of vividness and open space to the poem. The sonnet’s content up to this point had been somewhat confined to the meta-literary (the exploration of the act of writing, reading, the value of ancient texts, and so on). Now, the sky has opened, and Keats writes freely of the feeling of great literature, how it impacts and raises our consciousness. The feeling of that quick inhalation of breath, and holding, as a surprise takes hold, as we remember something we had long ago forgotten. I mean enchantment: an encounter with the other which somehow involves a renewed encounter with the self. This same feeling of openness and enchantment, arising as a result of stumbling upon something unexpectedly, Coleridge imagines to have taken place for his friends on their walking tour, in This Lime Tree Bower my Prison (1797). Coleridge pictures the English poet, Charles Lamb, emerging from the forest undergrowth to behold a wide landscape which had suddenly opened before them:

Now, my friends emerge

Beneath the wide wide Heaven—and view again

The many-steepled tract magnificent

Of hilly fields and meadows, and the sea [...]

(Stanza II, lines 21-24)And later in the poem, although Coleridge was forced to stay behind from the walk, he experiences the same feeling of elation and freedom, made possible through the use of his poetic imagination:

A delight

Comes sudden on my heart, and I am glad

As I myself were there!

(Stanza IV, lines 45-47)As I myself were there! Surely, this is the point of great literature. We immerse ourselves in this medium because of its capacity to transport us to other worlds; to new and unmapped areas of consciousness. For Keats, the lines of Homer had not merely registered with his mind in some passing aesthetic sense. No, he had truly felt like an astronomer watching the skies, discovering a new planet; truly felt the ‘wild surmise’ shared between explorers when new land was sighted on the horizon. It is this closeness, this sharing of feeling which makes the study and appreciation of literature a worthwhile pursuit. C.S. Lewis, in his An Experiment in Criticism (1961), sums this feeling up nicely:

We want to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as with our own... We demand windows. Literature as logos is a series of windows, even of doors. One of the things we feel after reading a great work is 'I have got out.'

Works cited:

Gittings, Robert. John Keats (biography). London: Penguin Books, 1968.

This is so fascinating! I had no idea Keats was training to be a surgeon! What I wouldn't give to have been there that night at Clark's to see Keats being roused into the poetic realm! Imagine if he had followed through with becoming a surgeon, that would have been devastating...

Very nice job. You captured and carried into the last analysis the powerful quality that good poetry or literature can do to us and for us and that is to transport us. "We have got out."

It is sobering to realize that when John Keats was my age he'd been dead for forty years. By his age I had not written a single poem. Andrew, on that very topic of coming close and seeing what the poet does here is a short poem of mine. https://westonpparker.substack.com/p/as-close-can-be