The eerie afterlife of ‘Sheep in Fog’ recalls the Underworld of Greek mythology, or the pre-creation void of the Hebrew Bible: returning to a time before the first sunrise, when darkness was upon the face of the deep. Plath swims in these dark waters, and slips beneath the waves.

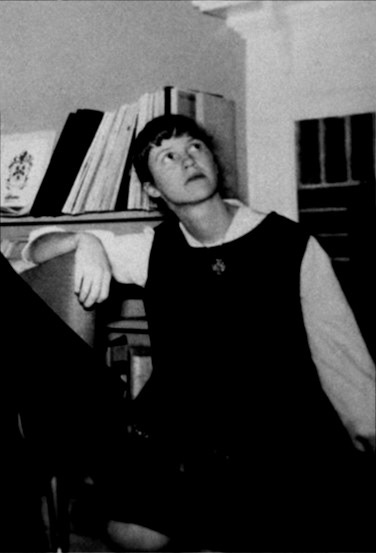

The short poem, Sheep in Fog, is the culmination of an amazing surge of inspiration that seized the American poet and novelist, Sylvia Plath, beginning in July of 1962. The results of this sudden increase in poetic output were published posthumously in her Ariel collection. Ted Hughes noted in a 1988 lecture, The Evolution of Sheep in Fog, that this surge of poetic output ended ‘abruptly’ with the drafting of Sheep in Fog in the beginning of December that same year. After this, ‘she wrote nothing at all for two months’, except to revise a poem—‘The Eavesdropper’—which was written on October 15th. In January of 1963, Plath wrote a few more early drafts of poetry, and completed the final revision of Sheep in Fog shortly before her death by suicide a few weeks later, on February 11th. We should consider that this rather dark poem was ‘preceded by weeks of fierce inspiration and confidence’ (Hughes, 2), the kind that produced Lady Lazarus, with its themes of transformation and rebirth. With Sheep in Fog, however, there is no rebirth, no hope of change or strength, only a continual stasis and darkening. One cannot shake off the feeling of quiet, hopeless resignation which seems to have taken hold in her thinking at this time:

Sheep in Fog

The hills step off into whiteness. People or stars Regard me sadly, I disappoint them. The train leaves a line of breath. O slow Horse the colour of rust, Hooves, dolorous bells— All morning the Morning has been blackening, A flower left out. My bones hold a stillness, the far Fields melt my heart. They threaten To let me through to a heaven Starless and fatherless, a dark water.

Professor Belinda Jack, in a lecture on Plath given at Gresham College, summarised the poem as exploring ‘feelings of loneliness and despair’, but especially noted the isolation of the poem’s speaker, who is left vulnerable in the expansive rural setting, surrounded by hills, horses, and ‘the far / Fields’. The speaker feels out of place, an object of judgement: ‘People or stars / Regard me sadly, I disappoint them.’ She notes that not only are the hills and fields disappointed in her, but also the heavenly spheres—her isolation is totalising and complete. It should be noted, too, that a third place—what Hughes has called an ‘eerie, afterlife feeling’—manifests in this poem. The ‘dolorous bells’ of the rust-coloured horse seem to announce a funeral; and as we read of her ‘bones hold[ing] a stillness’, and of the train leaving a slow ‘line of breath’ resembling a last exhale of the dying, we begin to see that the speaker is announcing her own imminent death. This passing is gradual but certain, with Hughes describing the poem’s depressing rhythm as rolling along with a ‘heavy, grieving momentum’ (Hughes, 2). Additionally, the speaker laments that All morning the / Morning has been blackening, a reversal of the oft-quoted Psalm 30:5: ‘weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning.’ As Belinda Jack notes in her lecture, for the speaker in this poem, the Morning brings mourning, and a gradual darkening, rather than light.

In the final stanza, the speaker acknowledges that these images ‘threaten / To let me through to a heaven / Starless and fatherless, a dark water.’ Plath was an atheist, though at times described herself as ‘a pagan unitarian at best’. The eerie afterlife of these final lines has more in common with the Underworld of Greek mythology, or in the pre-creation void of the Hebrew Bible: returning to a time before the first sunrise, when the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep (Gen. 1:2). Plath swims in these dark waters, and sadly finds herself slipping beneath the waves. Crucially, this heaven is also fatherless, perhaps because Plath had yet to reconcile herself fully with her father’s passing, a moment of intense and lasting trauma that she experienced at only eight years old. For this speaker, there is no Father who art in Heaven, only a sea of darkness echoing with dolorous bells. There is a similar sense of finality, of the ‘cold and planetary’, in the final lines of her poem written during the same period, The Moon and the Yew Tree:

And the message of the yew tree is blackness—blackness and silence.

Blackness and silence. Interestingly, towards the end of her life, Plath developed a fascination with Catholicism in particular, and seems to have identified with the lives of suffering saints, having read St. Thérèse of Lisieux and St. John of the Cross. Plath’s interest in the numinous would continue even into the final weeks before her suicide, where she may have experienced some kind of life-altering mystical experience. Judith Kroll, a Plath scholar who had consulted with Ted Hughes, noted that Hughes ‘remarked in conversation several times that during the last two or three weeks of her life [Plath] said something to the effect that “I have seen God, and he keeps picking me up” and “I am full of God’ (Ferretter, 112-113). Linda Wagner-Martin repeats this claim, writing that Sylvia had told Hughes ‘she had seen God several times during January and February’ of 1963 (Quoted by Holden-Kirwan, note 3, 306). What the true nature of Plath’s views on religion and the supernatural in her final days really were, it is impossible to know. And perhaps it is best that we do not know. Having read Sheep in Fog, however, which was revised in the weeks before her suicide, we may ask what kind of God this was that Plath had encountered; whether a strange, hollow and distant force, or perhaps a welcoming light and oneness more familiar to her Pagan Unitarianism. Whatever mystical experience Plath underwent in her final weeks, we must hope that she now floats peacefully atop the dark and planetary waters of the mind.

Works cited:

Ferretter, Luke. The Yearbook of English Studies, 2009, Vol. 39, No. 1/2. Literature and Religion (2009), pp. 101-113.

Holden-Kirwan, Jennifer. Christianity and Literature, Spring 1999, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Spring 1999), pp. 295-307.

Ted Hughes, The Evolution of Sheep in Fog (1988).

Lecture cited:

This was a very interesting read. Where have I been my entire life? Perhaps, if I read more of your submissions, I may answer that question for myself.

Such a beautiful poem and analysis.