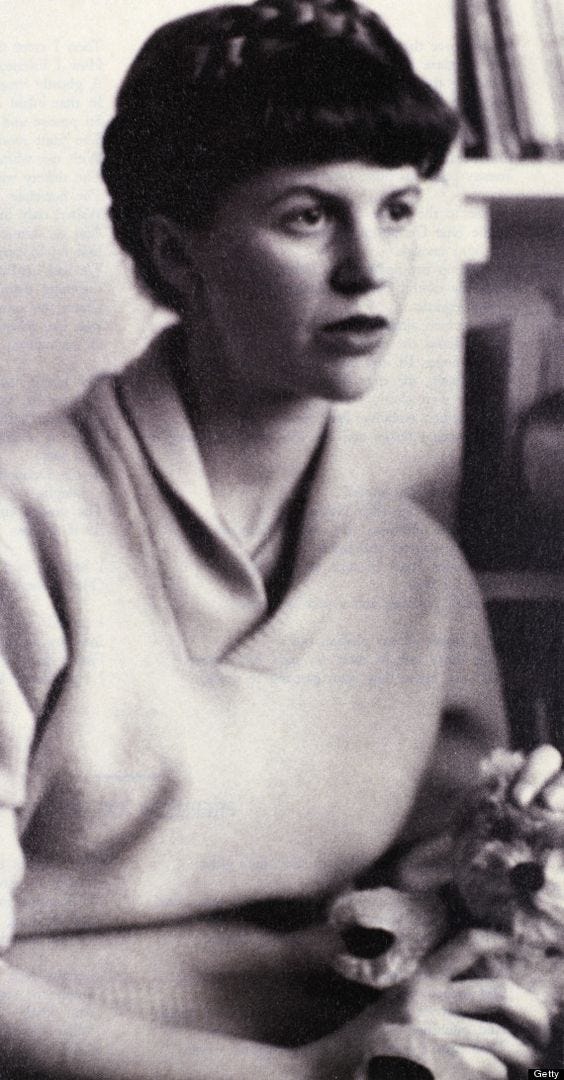

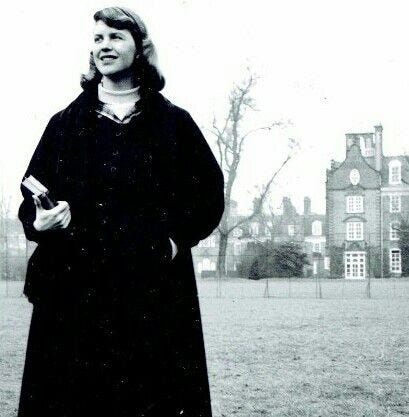

Lady Lazarus was written in October of 1962, just a few months before Plath committed suicide in February the next year. This text was among many poems written within the short period of time between the separation from her husband, Ted Hughes (following his affair with Assia Wevill), and her suicide. This extraordinary output of creativity, from which came the collection, Ariel (1965), is similar, I think, to John Keats’s bout of inspiration in the spring of 1819, wherein he wrote nearly all of his great Odes. Some spirit takes hold of great artists at various times in their life, it seems.

The title, Lady Lazarus, is derived from the New Testament, in the story of the raising of Lazarus from the dead in St. Luke’s Gospel (Luke 7:14-15). German symbols from the war period also feature prominently throughout the poem, and perhaps reflects the lasting sense of shame she held during her college years regarding the German ancestry on her father’s side. It must be noted that she indeed loved her father (who died when she was only eight), though her feelings towards him are complicated. Some part of her never forgave him for having left so soon. Her difficult and strained relationships with men also make their mark in these lines, with even the archetypal masculine figure, God (often presented as Father), being warned at poem’s end of her imminent resurrection and transformation. To introduce the poem to you all, I could think of nothing more appropriate than the poet’s own words, from a BBC radio interview in late 1962:

"The Speaker is a woman who has the great and terrible gift of being reborn. The only trouble is, she has to die first. She is the Phoenix, the libertarian spirit, what you will. She is also just a good, plain, very resourceful woman."

The great and terrible gift of being reborn. That gift of renewal is at the heart of Plath’s Lady Lazarus. The poem begins with the speaker, inspired by Plath herself, declaring ‘I have done it again. / One year in every ten / I manage it—’. One year in every ten she had either attempted to take her own life or had an accidental brush with death. Later in the poem, she explains the unfortunate sequence:

The first time it happened I was ten. It was an accident. The second time I meant To last it out and not come back at all. (Lines 35-38).

The first time she had come close to death was in a swimming accident, nearly drowning. The second time, at age twenty, she consumed forty of her mother's sleeping pills and hid away in a crawl space in the basement. Recounting the experience in the next lines, Plath recalls that she ‘rocked shut / As a seashell’. Notice the repetitive ‘sh’ sound; she really was a master of sibilance and alliterative writing. They would then ‘pick the worms off me like sticky pearls’, an evocative image symbolising that she had almost become worm-food. The setting and time of the poem, then, begins just after her third death, and second suicide attempt. She appears to have only recently died, lying in the morgue, awaiting cremation. Her consciousness is still here, though, narrating the experience for us. As the subject lay dead, the speaker goes on to describe her corpse using Nazi imagery, describing her state in terms recalling holocaust victims, whose dead bodies and belongings were repurposed in the war period to manufacture household items, such as lampshades, paperweights, and linen:

A sort of walking miracle, my skin Bright as a Nazi lampshade, My right foot A paperweight, My face a featureless, fine Jew linen.

This authorial move has garnered controversy, with some labelling the language as unnecessarily gross and insensitive, though I do not think that this was Plath’s intent.

The speaker then describes the peeling away of the cover concealing her deceased body. Again, this is all presumably taking place in a morgue-like setting, with family and friends gathered around:

Peel off the napkin O my enemy. Do I terrify? The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth?

Regardless of the state she now finds herself in, so far it is entirely expected. As the title suggests, throughout her life she has undergone death and rebirth, and this instance, she expects, will be no different. ‘Soon, soon […]’ she will be ‘a smiling woman’ again. She will resurrect, because ‘like the cat I have nine times to die […] And this is Number Three’. However, she does not exactly revel in this process. The glorious ending, the rebirth, is only made possible through the pain of having died. She sees the waste and trouble of it all:

What a trash To annihilate each decade. What a million filaments. The peanut-crunching crowd Shoves in to see Them unwrap me hand and foot— The big strip tease.

In the speaker’s apprehensiveness towards not only the process of dying, but also the inevitable judgement and attention derived from society, we can perhaps see that she views this process as in some sense inevitable; a horrible thing ingrained in her nature, set on a timer for the end of every decade. The striking monosyllabic line, ‘The big strip tease’, asserts the performative aspect of this process; that she is in some way providing entertainment to those around her by showcasing her brokenness for all to see. She feels taken advantage of by the ‘peanut-crunching crowd’, peanuts being a popular theatre snack during this period. Yet, strangely, the speaker embraces the performative aspect of her death:

Dying Is an art, like everything else. I do it exceptionally well. I do it so it feels like hell. I do it so it feels real. I guess you could say I've a call.

Although the act of dying here carries with it a theatrical tone, Plath identifies that the ultimate artistic value is to be found in her rising again from the dead. The resultant zealotry inspired in the masses upon seeing such a phenomena brings this point home:

It’s the theatrical Comeback in broad day To the same place, the same face, the same brute Amused shout: 'A miracle!' That knocks me out.

That people will scream, ‘miracle!’ upon her return to life seems strange to her. Whatever this process of death and rebirth is, Plath’s mocking and ironic tone indicates that she does not feel it is a bestowal of divine favour. Perhaps there is something far more elemental and mysterious at work, not simply explained by Christian categories of the miraculous. In the next lines, she anticipates that her resurrected body will be treated like the relics of some saint: ‘And there is a charge […] For a word or a touch / Or a bit of blood / Or a piece of my hair or my clothes’. The mystical/religious language deepens as the poem nears the end, and the climactic transformation nears realisation.

A final confrontation occurs in the last stage of the poem, as the subject appears to be on verge of being cremated. The medical professional organising the action is referred to in German terms, as ‘Herr Doktor […] Herr Enemy’ (Herr is German for Mr.). That she holds a kind of contempt or frustration towards masculine figures in her life is clear. Her father, who left her too soon; her husband, who mistreated her during their marriage and pursued an affair, instilled a sense of disillusionment with the male archetype. In the penultimate stanza, even the classically-masculine figures of western religion, God and Lucifer, are warned of her mounting dissatisfaction:

Herr God, Herr Lucifer Beware Beware.

The process of her cremation is vivid and almost unbearable to picture. She is a ‘pure gold baby / That melts to a shriek’, who ‘turn[s] and burn[s]’ in agony as the flames do their disintegrating work. Finally, she is reduced to ashes, the final stage of her destruction which allows for the possibility of her renewal. She imagines her Enemy flitting about through her remains to find anything of value, again reminiscent of holocaust imagery:

Ash, ash— You poke and stir Flesh, bone, there is nothing there— A cake of soap, A wedding ring, A gold filling.

In her collection, Ariel, there are scattered examples of odd religious and/or mystical imagery, which she utilises in order to communicate the stormy landscape of her inner life. In her poem, The Hanging Man, she was seized by ‘the roots of my hair by some god,’ and ‘sizzled in [the] blue volts like a desert prophet’, and this time in the final stanza of Lady Lazarus she undergoes a bright and terrible transition into something more than human, perhaps demonic:

Out of the ash I rise with my red hair And I eat men like air.

On one level of course this recalls the legend of the Phoenix rising from the ashes, reborn and transformed. According to the Ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, the Phoenix had yellow and red hair. The red hair may indicate something more sinister, however. The final line, ‘I eat men like air’, may indicate that this redness is such because she is drenched in blood. In any case, this is a resurrection, bright and powerful. Both God and the Devil, signifying the whole sweep of reality, both divine and human, must beware. There seems to be a real sense of violence, a spirit of revenge, pouring forth in this image. She has been raised, but seemingly not from any external power, but of her own Nature.

John Keats and Sylvia Plath are my favourite poets, each I virtually worship and have shrines of. Your narration of Plaths Lazarus is not only insightful, profound and fascinating, but so caring of her as a person. Love love this

I can only echo @Ella. Have always loved Plath. And your analysis of Lady Lazarus is worth re-reading more than once. Her work is in good hands with you, thank you for the delicate dissection. Wonderful.