After reading a great poem, I am more free to be myself; more free to find wonder in the world around me; more free to find grace in the commonplace. In this freedom we find recovery, what Aristotle called anagnorisis: a sense that we had just remembered what we had always known.

Many of you have asked, in private messages or in comments, for some guidance on how to approach the reading of great poetry. For my part, I can only point to and summarise what others far more capable than myself have said on the subject. On the matter of poetics (meter and structure), I have decided to dedicate a future post wholly to this subject. For this post, I would instead like to delve into what it is that poetry does for us, what is it good for, and so on. Harold Bloom’s wonderful essay, ‘The Art of Reading Poetry’; Bennet and Royle’s chapter on poetry in their introduction to English literature; and a few excerpts from the letters of John Keats, will all serve as key touchstones. For those who wish to follow up further, I provide a list of cited works below.

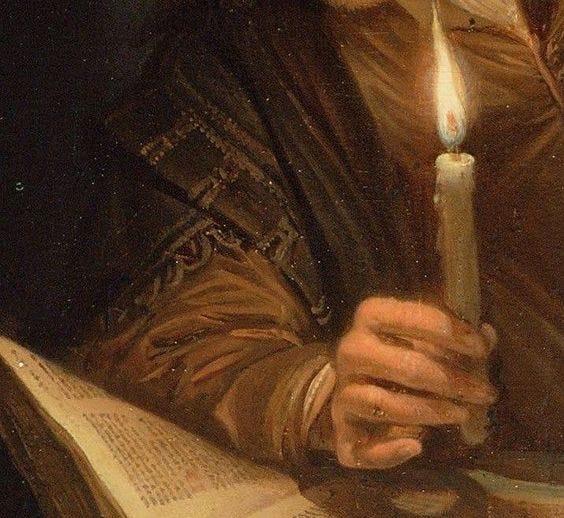

Delicate Eyes and Fingers

Before we get into the real heart of what makes poetry so enchanting and transformative, I thought it best to lay out some initial principles of reading poetry, inspired by Bennet and Royle’s wonderful introductory text, This Thing Called Literature (2015). First among these principles is the essential habit of close reading. The German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), provides a helpful definition of close reading in the preface of his book, Daybreak (1881): ‘[read] slowly, deeply, looking cautiously before and aft, with reservations, with doors left open, with delicate eyes and fingers’ (Quoted by Bennet and Royle, 24). In the spirit of Nietzsche’s words, it seems to me that we should be especially sensitive to the variation of possible meanings attendant in a word, phrase, or sentence. Consider the movement of a poem, its liveliness, its current; consider what philosophy of life, beliefs, or assumptions may vibrate or pulse beneath the surface of a text. Tease out the meaning of a poem, slowly, playing around with the edges of images and symbols. Notice what T.S. Eliot says here regarding poetic images, in his awe-inspiring Preludes (1917):

I am moved by fancies that are curled Around these images, and cling...

Consider how many fancies, associations, allusions, are ‘curled’ around poetic images. This is the transformative aspect of poetry, and we ‘cling’ to these impressions as they arise in a close reading, because they are the stuff of life.

It may seem like simple advice, but the best way that I have found to go about reading a poem closely is to annotate. It does not matter, really, how technical your annotations are at first, whether they be scanning for meter and syllable variation, or simply jotting down your personal thoughts in real time. That line, did it strike you in a particular way? Did your body react to the harmony of the alliteration, or the clearness of a metaphor? Write it down, and revisit it later. These are just some of the principles behind a close reading that I have found particularly useful, both as a student of poetry in university and an admirer of the medium in my free time.

What is the Point of Poetry Anyway?

Strictly speaking, I suppose, there really isn’t much point to poetry. The same pointlessness, perhaps, applies to the cinema and theatre—even the arts in general. If, by point, we mean their immediate practical application. But I think the relative uselessness of art is precisely the reason why its pursuit is so important to us. Oscar Wilde famously wrote, in his preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), that ‘All art is quite useless.’ Before we feel compelled to disagree with him, let us be sure we are understanding him first! While this was the last, most memorable line of his preface, let us also remember the first: ‘The artist is the creator of beautiful things.’ John Keats says something similar, in his famous Negative Capability letter, that ‘with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration” (Keats, 43). Archibald MacLeish, at the end of his Ars Poetica (1926), echoes this sentiment, writing that ‘A poem should not mean/But be’. And in the final lines of his Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819), Keats declares:

'Beauty is truth, truth beauty,' -- that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

So, art is useless and beautiful. Oftentimes what is beautiful in life—including poetry—is important to us precisely because it is useless. It is there to be admired, not puzzled over; its meaning should be felt, not taught. Sure, we learn principles of literary criticism, at university and elsewhere, and these techniques are very useful; but the really powerful stuff, what Bloom calls ‘the thing itself’, often is immediately apparent to the reader in a first or second reading. If anything, we embark on the academic study of poetry and literature precisely to cultivate a greater freedom and familiarity with the medium, so that the lines, symbols and metaphors are ever closer, ever more natural to us. We do not study poetics in order to make reading more difficult and obscure. Call to mind Keats again, who wrote in a letter to John Taylor in February of 1818, “that if Poetry comes not as naturally as leaves to a tree, then it had better not come at all” (Keats, 70). Here, I think, he means the process of writing poetry rather than reading it, but I think the same principle can be applied in our case.

The liberal arts (libertas, in Latin, meaning freedom) are valuable because we engage with them freely, of our own will, for the sake of exploration and wonder. It is a celebration of our humanness. “The work of great poetry is to aid us to become free artists of ourselves”, writes Bloom, and this artistic freedom entails a freedom of the self. After reading a great poem, I am more free to be myself; more free to find wonder in the world around me; more free to find grace in the commonplace. In this freedom we find recovery, what Aristotle called anagnorisis: a sense that we had just remembered what we had always known. This feeling of rememberance is explored beautifully in the final lines of T.S. Eliot’s Little Gidding (1942):

And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, unremembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning [...] Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea.

Half heard, in the stillness. That is when the real work is done to us; when the words come alive in our minds; when the images of Eliot, Tennyson, Keats, and Shakespeare perform their magical work of enchantment. But how am I somehow changed—more free—after reading a great poem? Because something in me has changed. This may sound spooky, even magical, but we all know the feeling, after we have read something so profound that it has broken us into pieces, and we are left to put ourselves back together again, somehow different than before. This feeling overcame me recently when reading the war poet, Wilfred Owen’s Futility:

Move him into the sun-- Gently its touch awoke him once, At home, whispering of fields unsown. Always it woke him, even in France, Until this morning and this snow. If anything might rouse him now The kind old sun will know. Think how it wakes the seeds,-- Woke, once, the clays of a cold star. Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides, Full-nerved--still warm--too hard to stir? Was it for this the clay grew tall? --O what made fatuous sunbeams toil To break earth's sleep at all?

Those final lines express such a startling pathos that one could hardly remain the same person after reading them. In his essay, Bloom recalls the ancient Hellenist critic, Longinus, writing that in great poetry “we apprehend a greatness to which we respond by a desire for identification, so that we will become what we behold” (Bloom, 21). We cannot help but identify with Owen’s world-weariness, his mingling of grief and fatigue. We, too, question ourselves, even the very meaning of human presence in this world, our place in the great History of Things. Something in us has changed. Though far removed from the battle-torn fields of Europe, our consciousness has mingled with Owen’s and as a result has become larger and stronger. “All great poetry”, according to Bloom, “asks us to be possessed by it”, and it is this same possession that “is the true mode for expanding our consciousness” (Bloom, 28). He then quotes the British philosopher, and member of the Inklings (Tolkien and Lewis’s merry band) , Owen Barfield, who stated that poetic wonder “arises from contact with a different kind of consciousness from our own, different, yet not so remote that we cannot partly share it.” (Quoted by Bloom, 28). It is from this sharing, this overhearing of other selves, that a real change in us can take place.

The art of reading poetry, for many of us, may not always have been our idea of a good time. Probably, we all remember those moments, perhaps in school, sitting through a literature class, bored out of our minds. However, I think, no matter how much we may have struggled to understand, at various times, precisely why poetry is so important, whether frustrated by its obscurity and archaic language, or distracted by the many diversions surrounding us at all times, there may have always been, as Stephen Fry notes, ‘some secret part of you [that] might have been privately moved or engaged’ (Fry, xvi). It is this feeling—prompted, perhaps, by some half-heard line—that proves Fry’s precept: ‘poetry is a primal impulse within us all.’

If you have made it to the end of this letter, I would like to say thank you :) And I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments below, whether regarding your opinion of this letter, or perhaps your own views on why poetry is so important to you.

Works cited:

Bennet, Andrew, Royle, Nicholas. This Thing Called Literature: Reading, Thinking, Writing. London: Routledge, 2015.

Fry, Stephen. The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking the Poet Within. London: Arrow Books, 2007.

Gittings, Robert. Letters of John Keats. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Poems cited, in order of appearance:

T.S. Eliot, Preludes IV (1917).

John Keats, Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819).

Archibald MacLeish, Ars Poetica (1926).

T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding, from Four Quartets (1942).

Wilfred Owen, Futility (1918).

Thanks for this Andrew! It was lovely to hear such a great defense of poetry's value. I agree with everything you wrote and also wanted to add that Keats and Wilde were both reacting to traditions in poetry that had trained readers to expect poems to function as vehicles of didacticism and moralism. Many 19th-century readers thought poems were written to teach them explicit lessons that they could apply to their own lives, so Wilde was being counter-cultural in insisting that art didn't have to do this.

I think sometimes people still prefer to have a lesson easily told rather than to wrestle with the abstraction of Beauty. I feel that a lot of contemporary poetry has gone back into overt moralism a bit. In one way, I understand this, because it makes reading poems easier if the message is obvious. But the process of freedom and recovery you described seems more limited if the reader doesn't have to participate as fully in recognizing the meaning. Anyway, thanks again and look forward to reading more from you!

The style/voice of your work is so enchanting, Andrew. Yet another rejuvenating post (as a fellow poet) just now—do keep it coming! ♥️