“I am myself, ironically, an atheist. And like a certain sort of atheist, my poems are God-obsessed, priest-obsessed. Full of Marys, Christs and nuns. Theology and philosophy fascinate me.” (Plath, Letters).

As I have become more familiar with Plath’s work in recent months, I have developed a great admiration for her sense of spiritual exploration. In this letter, I will explore the fascinating theological and philosophical dimensions of her life and work, and in doing so, hopefully lay the contextual groundwork for a deeper analysis of her poetry in the future. Below are many details of her interior life which, I must admit, surprised me (though in a good way), and my appreciation for her has only grown as a result. I hope you will feel the same.

Sylvia’s mother, Aurelia, was born and raised in the Catholic Church, but abandoned her childhood religion for Methodism during her college years, believing Catholic doctrine to be too repressive and stifling, especially for women. Plath’s father, Otto, born in Germany, was disowned by his grandfather, with his name being pencilled out of the family Bible, after he dropped out of Lutheran seminary. Part of the conditions of his being supported through college was his commitment to eventually becoming a Lutheran minister. Otto found, however, especially after encountering the work of Charles Darwin, that he could not in good conscience go forward with the plan. Later in life he became an atheist, and as Plath records in her therapy notes, this was much to the consternation of Aurelia. Otto Plath passed away when Sylvia was only eight years old, an event which she would grapple with continually throughout her life.

After Otto’s death, Sylvia was raised in the Unitarian Church, located in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Aurelia served in the Sunday school, and Sylvia even led the youth group. The two were active members of their Church community. This local Unitarian church was was far less dogmatic than, for instance, the Catholic or Anglican Church, and even encouraged doctrinal plurality among its members. One could even identify as an atheist and still be a practicing member of the Church, a detail which may serve as the context for Plath’s later description of herself as a ‘pagan Unitarian at best’ (Ferretter, 102). According to Luke Ferretter’s essay, Sylvia Plath’s Religion (2009), ‘One of the reasons that Plath valued the Unitarian church was that it provided her with a set of moral and social beliefs that she was able to hold without also believing in the supernatural existence of God’ (102). The character of Plath’s religious belief throughout her life may best be characterised as a reluctant atheism. Although at times she felt the allure of the spirit of religion, even exploring Catholicism in the years before her death (more on that below), she felt that an authentic conversion to one religious system or another was, all things considered, impossible.

Interestingly, there is something about Catholicism in particular, perhaps its pomp and ritual, which has attracted even the most libertine and modernist-leaning writers. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), famously, had a curious love affair with the Church throughout his life, and received the Last Rites as he lay dying. An 1876 diary entry of Liberal MP, Ronald Gower, recalls a meeting he had with the Oxford undergraduate, ‘[named] Oscar Wilde…a pleasant cheery fellow, but with his long-haired head full of nonsense regarding the Church of Rome. His room filled with photographs of the Pope and of Cardinal Manning’ (Taylor, Catholic Herald). Indeed, Wilde was scheduled to be received into the Church in 1878, but he changed his mind at the last moment, sending a box of Lillies in his place. His attitude to Catholicism, and religion in general, was playful and paradoxical, once remarking to a friend, ‘I am not a Catholic…I am simply a violent papist’. The French philosopher and novelist, Albert Camus (1913-1960), held a similar view. Speaking to a friend, Paul Raffi, he labelled himself an ‘independent Catholic’, saying ‘Catholic thought always seems bittersweet to me. It seduces me then offends me.’ (Royal, First Things).

It seduces me then offends me. Plath seemed to have experienced something similar. In the final months of her life, she engaged in a correspondence with ‘Father Bart’, a young Catholic priest studying literature at Oxford. Fr. Bart had reached out to Plath for advice on his poetry, and the two struck up a lively back-and-forth pertaining to their personal views on religion, and Plath happily offered him some of her thoughts on poetics. Plath even asked the priest to formally bless her, a gesture he was more than happy to perform. Delighted, Plath wrote to her mother, Aurelia, regarding her new acquaintance: ‘Imagine, a Roman Catholic priest at Oxford, also a poet, is writing me and blessing me, too!’ (Quoted by Holden-Hirwan, 300). Her dialogue with the priest provides a fascinating window into these final months of her life:

I am myself, ironically, an atheist. And like a certain sort of atheist, my poems are God-obsessed, priest-obsessed. Full of Marys, Christs and nuns. Theology and philosophy fascinate me. (Quoted by Ferreter, 103)Many examples of a verse ‘Full of Marys’ could be provided, though I think these lines from her later poem, The Moon and the Yew Tree (1961), in which she expresses her longing before a statue of the Virgin, may suffice:

How I would like to believe in tenderness— The face of the effigy, gentled by candles, Bending, on me in particular, its mild eyes.

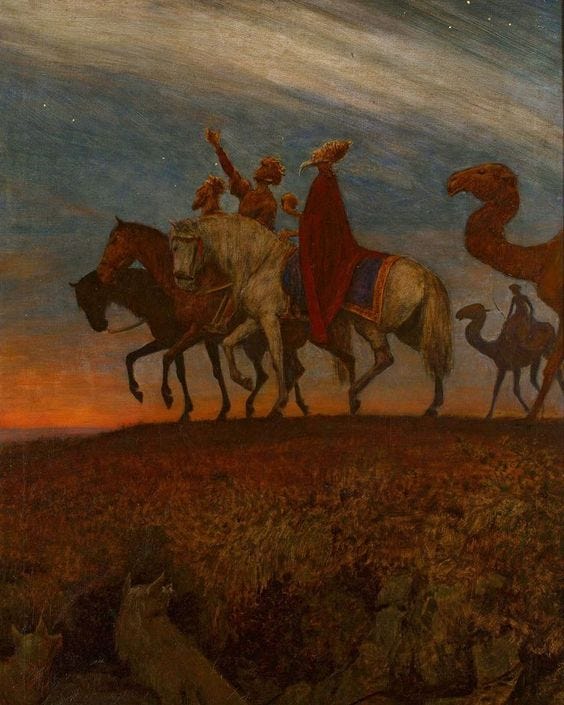

When Fr. Bart asked her what she herself believed in, she replied, ‘Myself. Now you will surely think I am unredeemable […] but do go on blessing me nevertheless’ (103). As Ferretter notes, ‘despite this formal rejection of the priest’s Catholic theology […] she nevertheless finds comfort in his blessings’. Indeed, this correspondence provides a window into the prevailing moral view of her life, a ‘moral commitment to the individual’s responsibility for creating his or her own life’ (104). Overall, I believe, her views on religion remained remarkably consistent. She believed in what Ferretter has called a ‘feminine materialism’. A little over a decade earlier, in July of 1952, she noted her thoughts on the Christian Science of the boy she was dating at the time, writing that she was ‘philosophically at the other end of the pole’, and was herself ‘a “matter worshipper”’ (104). According to reflections written to her friend, Marcia Brown, regarding Plath’s experience with the Anglican Church, a materialist metaphysic expressed more closely a feminine vision of the world. Ferretter summarises her reflections, writing that she thought ‘the Trinity is a man’s idea, putting the Holy Spirit in the place that should be occupied by the mother in the family circle’, further arguing that ‘the abstractions of religious beliefs are specifically male ways of thinking, doctrines that serve the interests of a society governed by men’ (105). In her poem, Magi (1960), she writes of those Wise Men that accompanied the birth of Christ, and asks, in the final line, ‘What girl ever flourished in such company?’

As well as feeling a persistent fascination with the mainstream of the Christian tradition (even while feeling the need to critique and interrogate this tradition), Plath also retained a lasting interest in certain Occult practices, such as the Ouija board, the tarot pack, crystals and astrology. These practices were introduced to her by her husband, Ted Hughes. Writing to her mother, she writes of her and Hughes’ mutual exploration:

[we] will become a team better than Mr and Mrs Yeats — he being a competent astrologist, reading horoscopes, and me being a tarot-pack reader, and, when we have enough money, a crystal-gazer. And in February of 1958, she wrote again: I must, this June beginning, learn about the planets and horoscopes to be in the proper starred house [...] tarot pack too. (Ferretter, 107).

In her letters she recalls playfully her mystical sessions with Hughes, and also of her scepticism of the reality of the phenomena behind the practices. Speaking of her Ouija experiences, she writes, ‘I wonder how much is our own intuition working, and how much queer accident, and how much “my father’s spirit”’. Ferretter sums up her interest in the Occult as follows:

Whilst she is interested in the Ouija board, the tarot pack, and astrology, that interest never turns into a belief in the realities posited by these practices. Writing a poem on the subject of the Lorelei because her 'Ouija imp' had suggested it was not, for Plath, a medium's responsibility to the spirits of the dead, but simply 'fun' (107).

Towards the end of her life, she developed a fascination with Catholicism in particular, and seems to have identified with the lives of the saints, having read St. Thérèse of Lisieux, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. John of the Cross. Interestingly, Wilde had found a similar comfort in Augustine’s Confessions, and the works of Cardinal John-Henry Newman, during his time in prison, and in the lead-up to his passing. Plath’s interest in the numinous would continue even into the final weeks of her life, before her suicide, where she may have experienced some kind of radically-altering mystical experience. Judith Kroll, a Plath scholar who had consulted with Ted Hughes, noted that Hughes ‘remarked in conversation several times that during the last two or three weeks of her life [Plath] said something to the effect that “I have seen God, and he keeps picking me up” and “I am full of God’ (112-113). Linda Wagner-Martin repeats this claim, writing that Sylvia had told Hughes ‘she had seen God several times during January and February’ of 1963 (Quoted by Holden-Kirwan, note 3, 306).

What the true nature of Plath’s views on religion and the supernatural in her final days really was, it is impossible to know. And perhaps it is best that we do not know, too intimately, the convulsive landscape of her interiority during that period. It suffices, in my view, to know that throughout her life she maintained an eclectic taste, consulting theology, philosophy, and even the occult, as alternative ways of seeing, never seeking to close or restrict her experience of life and the world. Perhaps her views are best summed up in this description by Ferretter, in which he paraphrases a letter that she wrote in August of 1950, to her student friend, Eddie Cohen:

She told him that she did not go to church much because she believed that each individual is responsible for working out his own purpose and destiny, that she could be labelled as an atheist, but that she nevertheless had deep respect for life and for human potential. These are the beliefs that she would later describe simply as her 'humanism' (Ferretter, 102).

Works Cited

https://catholicherald.co.uk/oscar-wildes-long-journey-to-catholicism/

Ferretter, Luke. The Yearbook of English Studies, 2009, Vol. 39, No. 1/2. Literature and Religion (2009), pp. 101-113.

Holden-Kirwan, Jennifer. Christianity and Literature, Spring 1999, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Spring 1999), pp. 295-307.

I loved how you drew in Wilde and Camus as well. It was quite an informative piece and since never have I focussed much on her religious affinities before so this brought in a new aspect of perceiving Plath's work. Thank you!