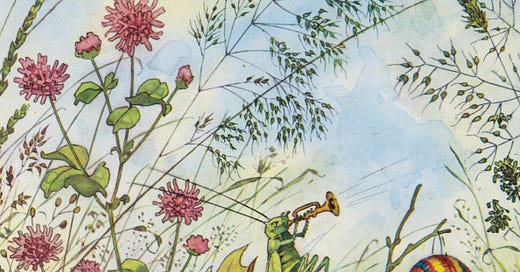

Keats lowers from the heights of philosophic speculation to dwell briefly amidst the trees, where birds drowse lazily in the cool to hide from summer heat. Then he follows a small voice chirping from the grass below: ‘That is the Grasshopper’s.’

The Poetry of Earth is never dead. So proclaimed the English Romantic poet, John Keats (1795-1821), in the opening line of his early sonnet, On the Grasshopper and Cricket (1818). For me, it is a poem that holds special significance, and is one of the first poems (alongside Bright Star) that I committed to memory. Robert Gittings recounts in his biography of Keats that the poem’s subject of ‘Grasshopper and Cricket’ was proposed ‘by the evening fireside’ in the quiet of a cottage, by Keats’ poet friend, Leigh Hunt, in a friendly competition. Here are a few thoughts on this memorable poem, one that shines with such natural vitality and simple joy:

The Poetry of earth is never dead:

When all the birds are faint with the hot sun,

And hide in cooling trees, a voice will run

From hedge to hedge about the new-mown mead;

That is the Grasshopper’s—he takes the lead

In summer luxury,—he has never done

With his delights; for when tired out with fun

He rests at ease beneath some pleasant weed.

The poetry of earth is ceasing never:

On a lone winter evening, when the frost

Has wrought a silence, from the stove there shrills

The Cricket’s song, in warmth increasing ever,

And seems to one in drowsiness half lost,

The Grasshopper’s among some grassy hills.The Poetry of earth is never dead. According to Gittings, this line in particular ‘brought generous praise’ from Hunt, even if Keats still thought that his friend’s poem was more impressive. It is a punchy opener, and imbues the rest of these lines with a loftiness and honour that would perhaps otherwise be missed in the pastoral tone of the following lines.

From the outset, the poem’s spacial dimension warrants some attention. Keats begins in the clouds with an almost philosophic statement: earth has an eternal Poetry that will never fade or be lost, a harmony and intelligibility that will long survive the capacity even of the poet to tell of it. The poem then lowers from these heights to dwell briefly amidst the trees, where birds drowse lazily in the cool to hide from summer heat. Then the poet’s eye follows a small voice chirping from the grass below: That is the Grasshopper’s. Already in the first handful of lines we have moved down three levels of space, a testament to Keats’ exceptional handling of place and setting.

Often, the Grasshopper is heard before it is seen, and so it is with this poem. Its chirp and presence almost becomes audible to us; we hear it further off as he runs ‘from hedge to hedge’, revelling ‘In summer luxury’. In the middle of the sonnet, ‘when tired out with fun’, the Grasshopper ‘rests at ease beneath some pleasant weed.’ This image calls to mind Keats’ earlier sonnet, To One Who Has Been Long in City Pent (1816), in which the subject, revelling before ‘the open face of heaven’, lazily ‘sinks into some pleasant lair / Of wavy grass.’ A certain kind of practiced idleness is important for Keats, and in his view is key to a poet’s creativity, as is evident in his Ode on Indolence (1819). In the heading to this Ode, he quotes Mathew’s Gospel, wherein Christ refers to the lilies of the field as models for human behaviour: ‘they toil not, neither do they spin’ (Mt. 6:28, KJV). In the volta (or turn) of the poem, which in the Petrarchan sonnet form usually occurs around line 9, Keats repeats a variation on the opening line: The poetry of earth is ceasing never, then transitioning from the full heat of a summer’s day to the chill of ‘a lone winter evening’. Like Coleridge’s winter cabin in Frost at Midnight (1798), Keats writes that ‘the frost / Has wrought a silence’, allowing for the Cricket to be heard ever more distinctly, swelling into a crescendo of sense in the final lines. It is worth mentioning that in his poetry Keats often transitions from one time of day to the next, sometimes beginning when the sun is at its zenith, and ending when evening settles in. In To One Who Has Been Long in City Pent, his subject begins ‘in the smile of the blue firmament’, and ends ‘returning home at evening […] mourn[ing] that day so soon has glided by.’ And in his sonnet, The Day is Gone (1819), he laments the passing the day’s ‘Warm breath’ and ‘light whisper’, and ends with ‘the dusk’ and ‘woof of darkness thick’. However, in On the Grasshopper and Cricket, while there are many transition points to notice—day to night, heat to cold—there is one presence that is carried over from octave through to sestet: ‘The Cricket’s song, in warmth increasing ever.’

Unmatched lyrical beauty in Keats wonderfully captured in your article