A spirit of curiosity had seized him after midnight, that special time in literature and mythology where the unfamiliar and strange takes place, where the boundary between our world and the next appears most fragile and unstable. In Shakespeare it is the witching hour; a time when Hamlet encountered his father’s spirit on the ramparts; when Macbeth was led by bloody dagger to Duncan’s bedroom; when Lear, upon the heath, fought against the storm with great sound and fury.

Edgar Allan Poe’s immortal poem, The Raven, was met with widespread acclaim upon its publication in the New York Evening Mirror in Janaury of 1845. The poem is shot-through with unusual alliteration, strange language and supernatural images. Throughout the narrative we witness the unravelling of what I have come to see as entangled opposites: imagery that is both light and dark, saintly and demoniac, human and divine. Ted Hughes, in The Snake in the Oak (1996), an essay on Coleridge’s poetry, wrote of Coleridge that he experienced Two Selves: A Christian self and a Pagan self. It seems to me that a similar dynamic is on display in Poe’s The Raven, and the coming together of these themes amounts to a striking experience for the reader that is hard to forget. The American poet, N. P. Willis, in the preface of the Evening Mirror edition, wrote the following, which I am sure we all agree with whole heartedly: ‘It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it.’

The poem begins ‘Once upon a midnight dreary’, as a young scholar tries to nurse his grief with books. Still mourning the passing of his lover, the scholar, [W]eak and weary,’ attends to ‘many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore’. Until, that is, his solitude is interrupted by ‘a tapping, / As of one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.’ The first stanza begins with a disruption, and the reader shares in the scholar’s curiosity. What could it be?

"'Tis some visitor," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door— Only this, and nothing more."

And nothing more. The scholar returns to his melancholy, admitting that he had ‘vainly […] sought to borrow / From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore.’ Lenore being a name for his late lover, a ‘rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name[d]’, though now in this mortal realm she is ‘Nameless here for evermore.’ In many ways, this poem feels like a searching for that name, amidst shadows and vaporous forms, the young scholar reaches for some memory of her. This it is, and nothing more.

And yet, a certain intuition prompted him to open his chamber door:

here I opened wide the door;— Darkness there and nothing more. Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before; But the silence was unbroken, and the darkness gave no token, And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, "Lenore!"

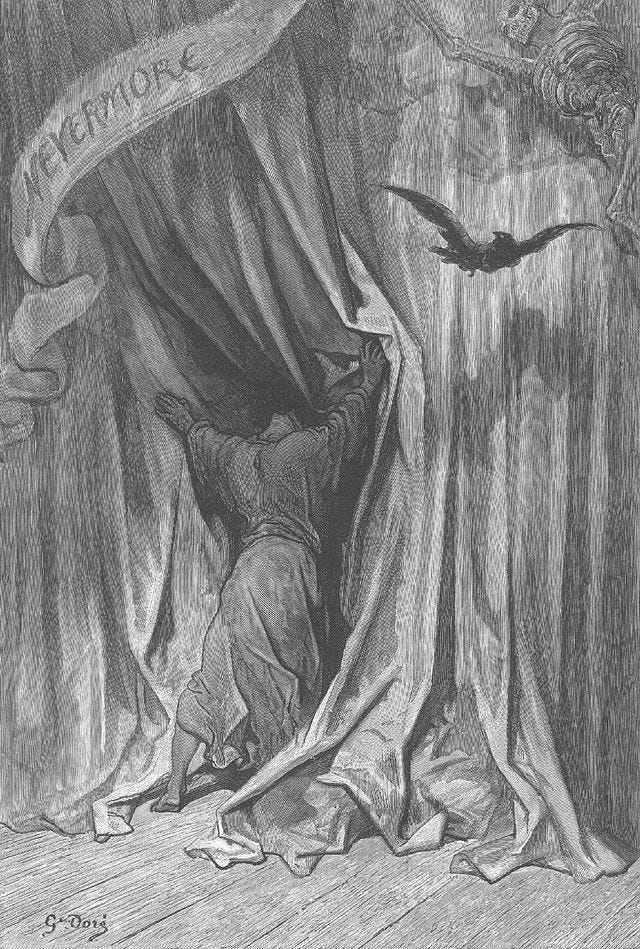

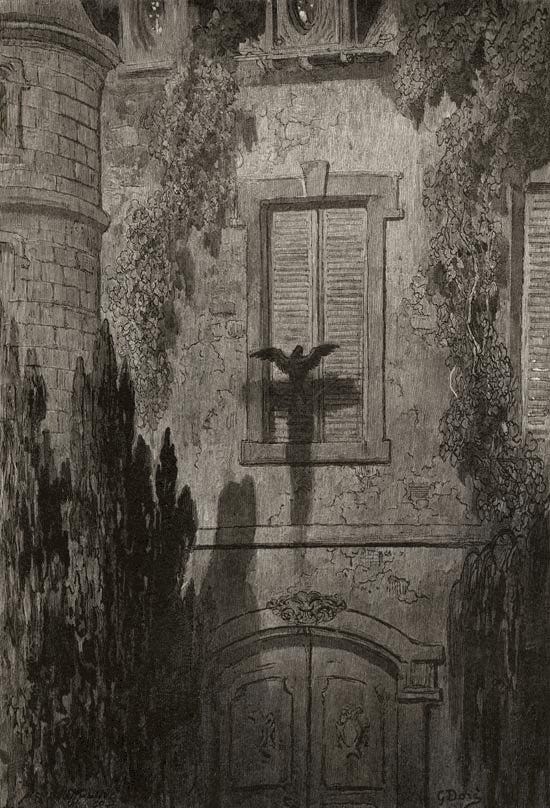

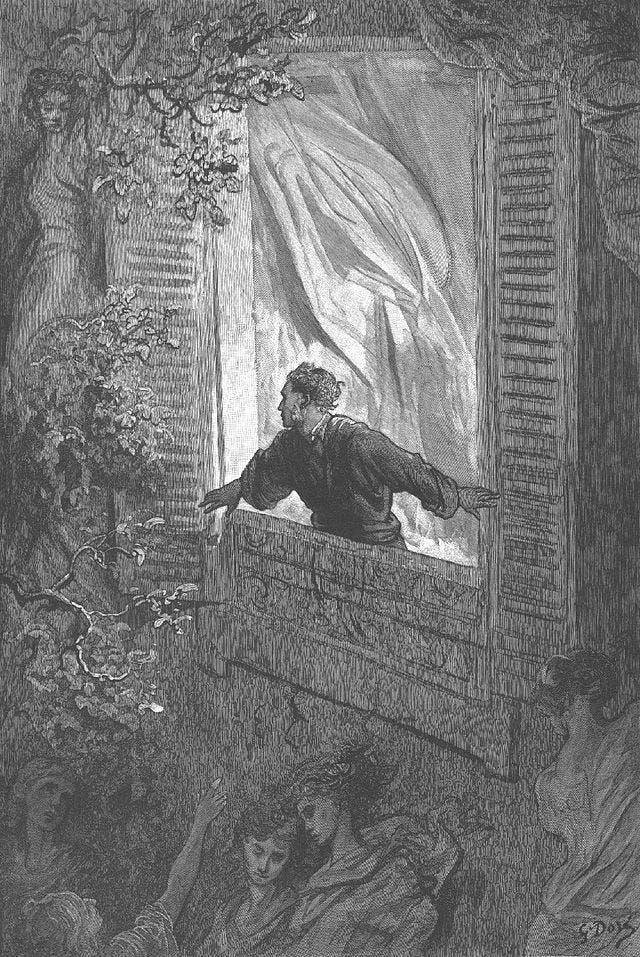

Interestingly, there is a parallel scene in Poe’s earlier short story, The Tell-Tale Heart (1843), wherein the protagonist, night after night, would peer into his would-be victim’s bedroom, a room ‘as black as pitch with the thick darkness’, and hold his head there, waiting and watching in the dark. While the man from that story had searched for violence, the young scholar in The Raven looked only for his lost love. “Lenore!” he whispered, and was met with only an echo. “Merely this and nothing more.” Returning to his chamber, the tapping sound was heard again, this time most cleary from the window. The scholar’s curiosity lead him to fling open the shutter, and we are introduced to one of the most enduring characters in all of modern literature, The Raven:

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

A spirit of curiosity had seized him after midnight, that special time in literature and mythology where the unfamiliar and strange takes place, where the boundary between our world and the next appears most fragile and unstable.

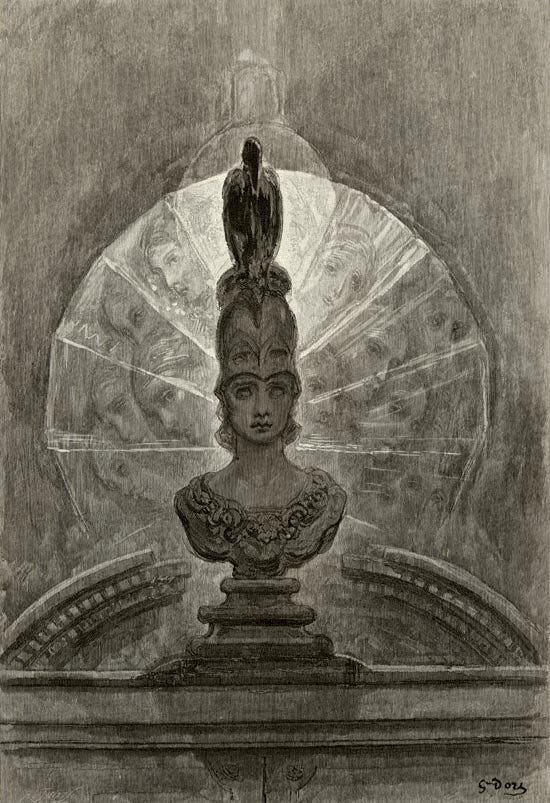

In Shakespeare it is the witching hour; a time when Hamlet encountered his father’s spirit on the ramparts; when Macbeth was led by bloody dagger to Duncan’s bedroom; when Lear, upon the heath, fought against the storm with great sound and fury. Additionally, the Raven has been a classic symbol in literature throughout history. Its presence often signifies loss and ill-omen, but its application is not so clear in this poem. We are helped out a little by the bird having landed atop the bust of the Greek goddess, Athena (Pallas), associated with wisdom and insight. It is those traits—those of prophecy and intuition—that the Raven seems most to embody in the following stanzas. The resonance of pagan antiquity is likewise felt by the young scholar, as he declares that the ‘Ghastly grim and ancient Raven’ has wandered in ‘from the Nightly shore […] the Night’s Plutonian shore!” Pluto was the god of the underworld in Roman mythology, and the ‘shore’ is understood by critics to represent the river Acheron, the place of transition between life and death. The scholar asks ‘what thy lordly name is’, investing the bird with a kind of regal and authoritative status as a messenger from this underworld. The Raven replies: ‘Nevermore.’ What this ‘bird of yore’ could possibly mean in its repetition of the word in the following verses, the man struggles to guess. “Doubtless”, he guesses, “what it utters is its only stock and store”, a learned behaviour picked up from a previous owner. But a part of him cannot believe the answer could be so simple:

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore—

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of yore

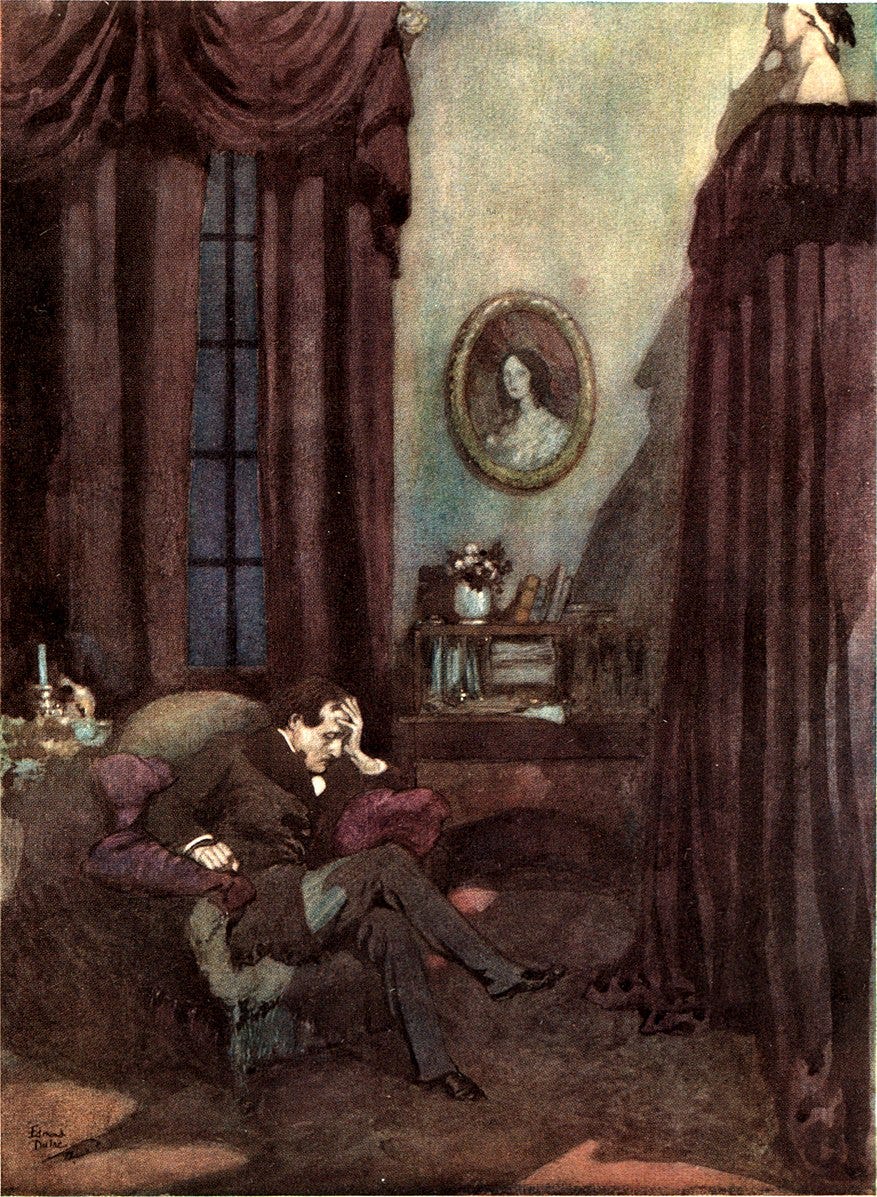

Meant in croaking "Nevermore."Taking his place on the chair, he sat wordless, ‘engaged in guessing’, enchanted by ‘the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core’. The bird seems to be a herald from a higher world, or a lower one, here to remind the young scholar of something he apparently needs to hear in this stage of his life. But what is it? There he ‘sat divining, with my head at ease reclining / On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light’ overshadowed. Finally, unnerved by the extreme silence, or perhaps seized by some sudden bout of courage, the young scholar gives an impassioned plea for any knowledge the Raven may have about his late lover:

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil—prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore—

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore."

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."The scholar wishes for news of Lenore beyond the borders of this world, (using the Arabic word, Aidenn, which means Eden or Paradise). He wonders now if this bird is a ‘thing of evil’, and in the previous stanza suggested it may have been sent by the ‘Tempter’ himself, i.e., the devil, now having used various images from the Christian imagination as well as pagan antiquity. The synthesis of religious traditions is notable. On the one hand, he imagines censers and incense ‘Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor’, and on the other that there has been a visitation from the underworld of Roman mythology, a bird sent from Pluto himself. The scholar brings these worlds together, appealing to a common Heaven and a common Father, shared even by the mysterious bird, appealing to ‘that Heaven that bends above us [and] that God we both adore’. The Raven, however, repeats its only cry, ‘Nevermore’. Sent into a desperate fury, he attempts to drive the bird from his chamber: ‘Be that word our sign in parting, bird or fiend!’:

"Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore! Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken! Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door! Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!"

‘Nevermore’, the Raven replies. And yet, the bird remains, ‘still […] sitting / On the palled bust of Pallas just above my chamber door’. Why has it not left him after enduring such scorn and violence? The young scholar believes it has told him nothing of importance, has delivered no supernatural insight or message, and has left him in a more confused and helpless state than he was before. At least he had been safe in his books, although miserable. But he had heard a knocking from outside of himself, an interruption of his normal life, an inviting gesture from the beyond. Peering into the dark, he had looked for Lenore, and still looked expectantly when greeted with only an echo. He was holding out for something more. Strange things may happen when we speak into the dark—the place of chaos and potential—with faith and expectation. In the Hebrew creation story, God spoke His first recorded words when ‘the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep’. The young scholar speaks into that same darkness outside his chamber door, and at first is disappointed by what he has found: an echo of himself. And yet, The Raven continues to knock from the window lattice, a place he had not thought to look. He must fly open the curtains and let her in. We must invite her into our home and learn from her.

After failing to force the Raven out from his chamber, the scholar then sees the bird in a new light, now appearing terrible and lordly, as one who holds answers, though perhaps not in the form that he had expected. The scholar, trained in language and books, had looked for his answer in words. In the final stanza, the Raven gives its message by way of presence, rather than verbalisation. In a mysterious act of perception, the man peers into its eyes, eyes which tell of demon dreams. And with the lamp-light refracting its shadow across the floor, his soul laid bare and true:

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

Wonderfully written. Insightful explanation of a great lyric poem.

It interesting: I always imagined the narrator to be an old antiquarian, somewhat well-to-do, regretting his lost love, nearing the end of his life which he spent in the nepenthe of his books. Kind of a Mrs. Haversham figure. And the raven come to wake him back to active misery.