In the late 19th and 20th century, many literary figures were haunted by the spell of ancient Christianity. Writers such as Oscar Wilde, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, and Evelyn Waugh, converted either to Catholicism or to its Anglican equivalent, Anglo-Catholicism. What is it about this religion that continues to enamour the heart and mind of the poet and philosopher, those of us who are contemplative and curious by nature? In our search for meaning, would it be a mistake to go back to Church?

Today there is a surge of interest in Catholicism1 and in the equally ancient Eastern Orthodox Church,2 where parishes are reporting rising attendance and conversions, especially among the young. Many of us know at least somebody in our lives that we discovered had (all of the sudden!) converted to one of these Churches, or is at least inquiring in some way. There is an anecdote that is quite popular in Catholic circles today: that a great number of philosophy graduates end up converting to Catholicism. I too have been tempted by the Church, but find myself agreeing (reluctantly) with Camus, who wrote that ‘Catholic thought always seems bittersweet to me. It seduces me then offends me. Undoubtedly, I lack what is essential.’ What is it about ancient Christianity, particularly Catholicism, that seduces us? That enamours the heart and mind of the poet and philosopher, those of us who are contemplative and curious by nature? Answering this question will not only help us to better understand the role of the numinous in our own creative lives, but will also allow us to interpret with clear eyes the revival of interest in ancient religion that is taking place today.

Is this curiosity, prompted perhaps by what Evelyn Waugh called ‘the twitch of the thread’, so surprising? Surely we have all noticed that there are hints and glimmers in everyday life of something vital missing from our world. The enchanted realm of ritual, of sacred space, is receding from view. Some point out that the majority of converts to Catholicism and Orthodoxy are young men, dismissing this phenomenon as nothing more than a temper-tantrum by those who wish to once again exert power over women. For some, this may be an unconscious (or conscious) motivator, but I find it unforgivably cynical to overstate this point as somehow being representative of the rule.

The truth is that there is a mental and spiritual ennui, a tiredness of life, that has established itself in the West, an everyday exhaustion that cannot be fixed by new mental health programs or state-sponsored initiatives. Look around us, and you will see the desolation taking hold. Here in Australia, suicide is the leading cause of death among young people aged 15 to 24. We are losing many things which make us human: community, shared ritual, a common story. And some may argue (perhaps convincingly) that the common story that has kept us together for millennia—namely, Christianity—is simply untrue, and therefore it cannot be the answer for our current dilemma. Are we really going to go back to believing all that?

The Spell of Catholicism In the Fin De Siècle:

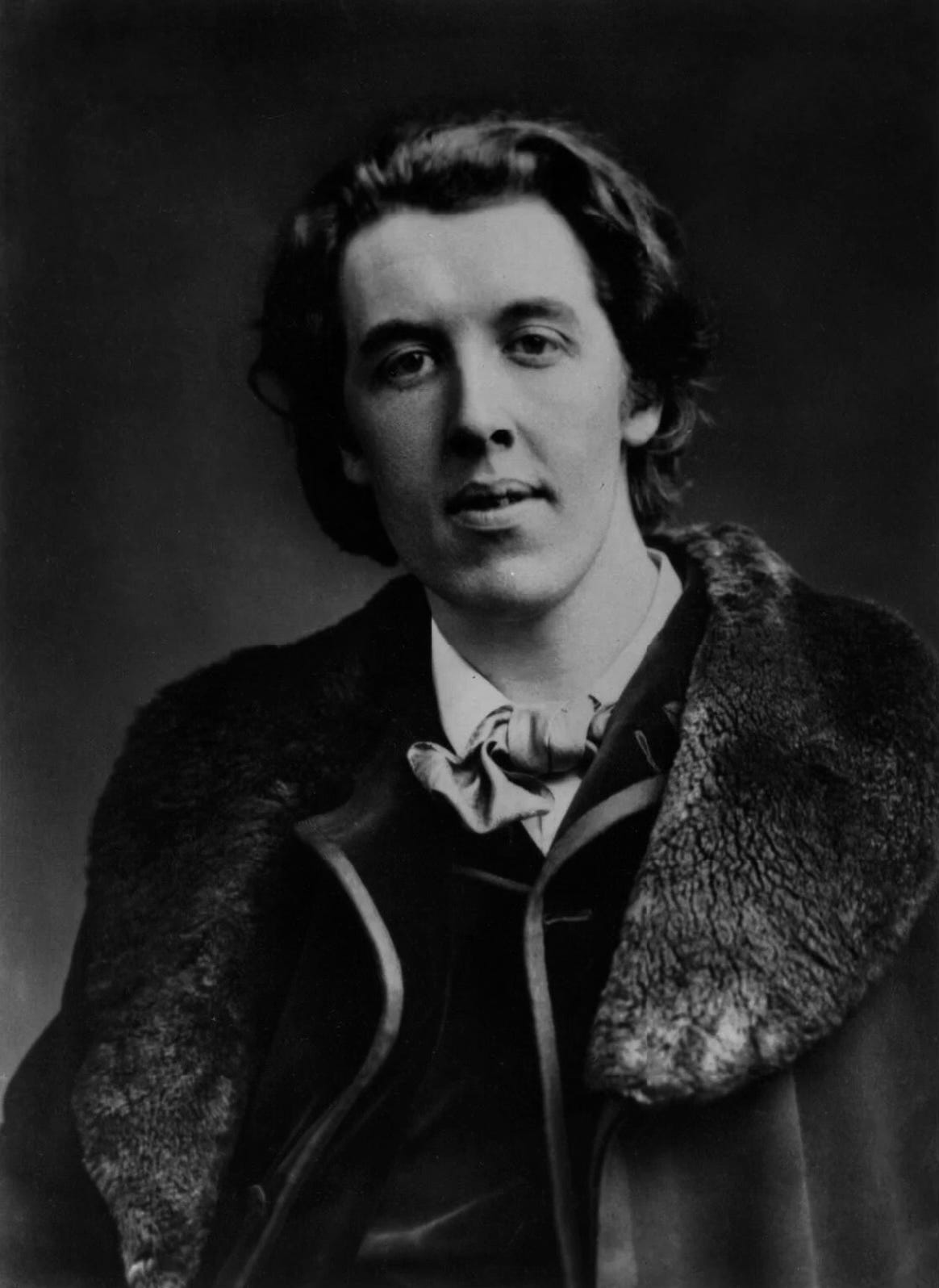

At the turn of the nineteenth century, many literary figures of the “Decadent” school of literature, much to the surprise of their contemporaries, began converting to Catholicism. Walter Pater, a leading influence in this period, wrote in his essay, Pascal (1894), that “[m]ultitudes in every generation have felt at least the aesthetic charm of the rites of the Catholic Church”. These figures of the Fin de Siècle included, but were not limited to, Lionel Johnson, Oscar Wilde (including his lover, the poet Lord Alfred Douglas), and John Gray. The twentieth century also saw many other notable scholars and poets who either converted to Roman Catholicism or to its Anglican equivalent, Anglo-Catholicism, such as T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, Muriel Spark, and Evelyn Waugh.

The “Decadent” movement in literature and art of the late nineteenth century was one marked by an excessively sensual and aesthetic taste. In the eleventh chapter of Oscar Wilde’s novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), there are whole pages devoted to opulent descriptions of precious stones, jewels, trinkets and luxurious scents. One comes away feeling overstuffed, which is precisely the point: Dorian becomes like the patrician at a Roman banquet who tickles his throat with feathers to make room for more dainties. Some choose to skip this part of the novel, but I feel that its excessiveness helps to illustrate the heart of “Decadence”, the end result of Walter Pater’s belief in ‘Art for Art’s Sake’. Interestingly, as Claire Masurel-Murray notes in her journal article on Conversions to Catholicism Among Fin de Siècle Writers (2012), ‘the “Decadent” movement probably counts in its ranks more [Catholic] converts than any other school in the history of British literature.’3 How fascinating! That these writers in particular would feel so keenly the allure of the Church is in need of explanation. They must have had a guilty conscience, some might say. While this may have been partly the case for some of these writers, we will see that their reasons were far broader and more universally human.

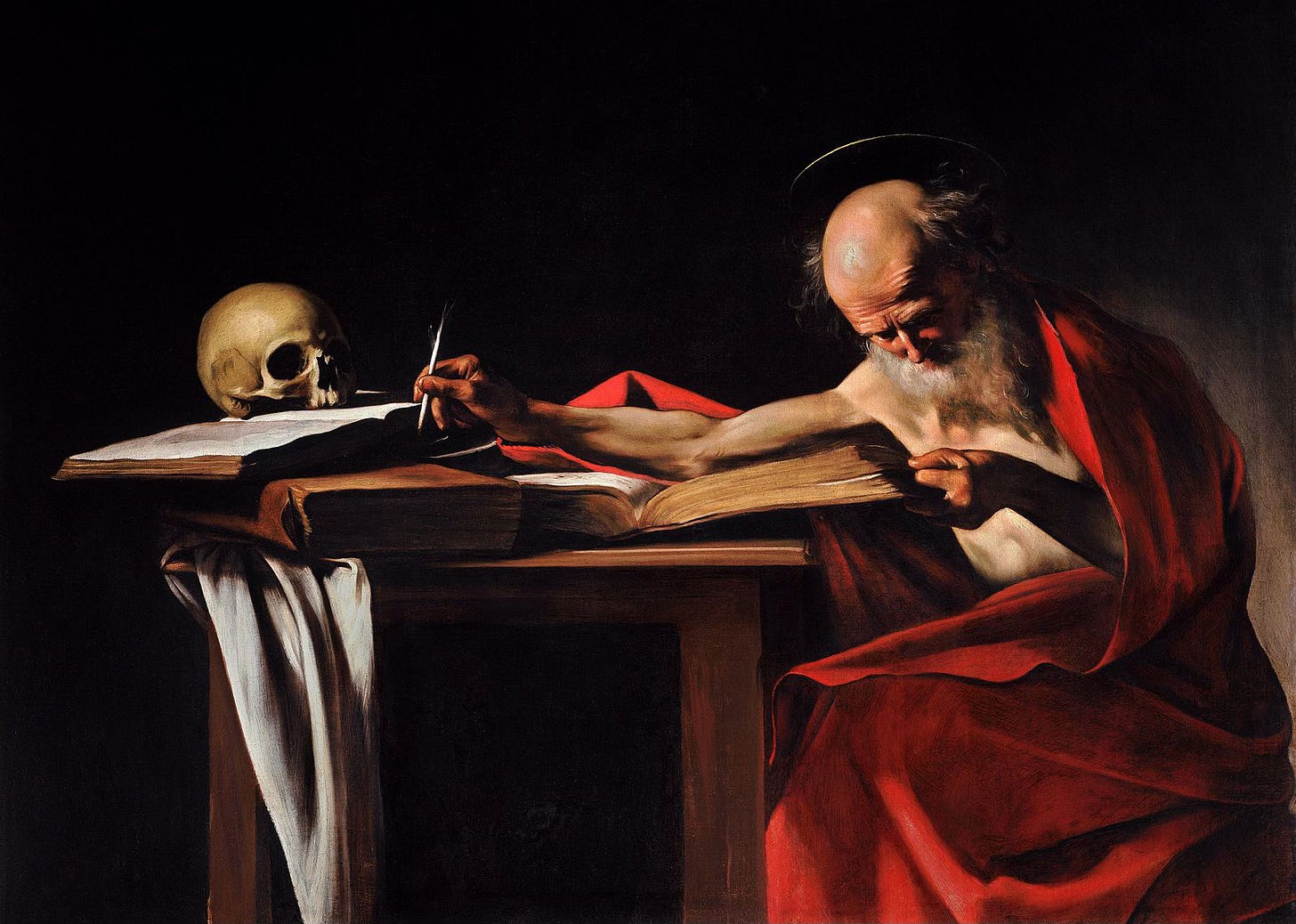

The writing of Walter Pater (1839-1894), an English essayist who wrote glowingly of Catholic aesthetics, strongly influenced the fin de siècle writers, in many ways laying the path for their journey towards Rome. Pater provided them with a framework—'Art for art’s sake’—within which to place their natural appreciation of Catholic imagery, symbolism, and ritual. Masurel-Murray describes what exactly it was about the Catholic Church that allured these literary figures:

The fascination for the macabre, the combination of sensuousness and mysticism, the search for refined sensations, the desire to create compensatory worlds in order to flee a reality that is perceived as unbearable—all these elements are indeed echoed in a certain kind of fin de siècle Catholic devotion that focuses on the cult of martyrs, of Christ as Homo Dolorosus and of the Virgin of the Seven Sorrows, as well as the formal beauty of the liturgy, on legends, on miracles and on apparitions […]

All these elements, she continues, ‘the Decadents promptly integrated into their imaginary universes and their mythical apparatus.’4 In contrast, the Church of England had become a kind of civic religion whose highest calling was ‘respectability’, and did not appear to these writers to embody authentic religious experience, at least nothing that could adequately counter the spiritual dryness of modern life. As an aside, I have found myself wondering about the inherent limitations of State Churches, in terms of their broad appeal. In my country, if there existed a ‘Church of Australia’, I would be repulsed. In any case, there are other factors at play, such as history and heritage, which account for the Anglican allure, including its special relationship with England’s thousand-year-old monarchy. After all, the first-generation Romantic poets, such as Wordsworth and Coleridge—who nobody could accuse of lacking an ear for mystery—eventually found a home in the English Church. But for the fin de siècle writers who were attracted ‘to mysticism, the occult, esotericism’,5 the Church of England, although it retained a certain degree of liturgical dressing, still lacked the otherworldliness of Catholicism. Oscar Wilde summarised their dilemma in this manner: ‘the Catholic Church is for saints and sinners alone —for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do.’

Don’t We Know Too Much?

Coinciding with this period were developments in the natural sciences and in the popularity of critical theory from Germany, both of which undermined the infallibility and authority of the Biblical texts. The approach to the Bible known as ‘Higher Criticism’ utilised the ground-breaking Historical-Critical Method, an approach which treated Scripture in the same manner as a secular piece of literature. Having emerged from the German theological schools of the late eighteenth century (that is, the Protestant stronghold of Europe), the Catholic Church firmly rejected the method’s unacceptable findings: that the Bible was not inerrant, and was in fact all-too human in origin; that its composition took place over many centuries and involved redactions, changes, and even blatant manipulations.

The Catholic Church remained largely unaffected by these views, treating them as obviously heretical—a Godless method which was only further evidence of the rotten fruit produced by the Reformation. Catholicism thus retained its view of the infallibility of the Church and the Bible, and the authority of the clergy, therefore retaining its street-cred as the most authentic expression of ancient religion in England and Europe. To literary figures of the time searching for the ‘real thing’, partly in reaction to a growing spiritual dryness taking place in the culture, the protestants had become ‘de-fanged’. To the fin de siècle writers, the Church of England was ceding too much ground to rationalism. Religion was religion, magic was magic—either have the real thing or give it up altogether. As Murray points out, ‘Catholicism […] appears as the vehicle of a form of resistance to the secular and disenchanted vision of the world which is spreading at the time’, and coupled with its ‘considerable artistic and cultural heritage’, it emerged in the late nineteenth century as the vehicle for re-enchantment:

The cult of saints, the devotion of Mary, the belief in miracles and apparitions, the sacraments, all these elements sanctify reality and introduce a mythical dimension into the way things are perceived.

Indeed, Catholics were considered by the Decadents ‘as the new dissidents of modern civilisation’.6 Today, Catholic converts often seem themselves as ‘counter-cultural’. It is the same phenomenon.

The Influence of Cardinal Newman

But William Pater’s Catholic interest was one of ‘impressions and emotions’, rather than of a theology that was rationally considered.7 Because his attraction to the Church was limited to aesthetics, he never converted. Above all it was John Henry Newman, a figurehead of the Tractarians, a group that sought to re-Catholicise the Church of England, that moved fin de siècle writers beyond a mere appreciation for aesthetics and into a space of genuine conversion. According to Murray, Newman ‘was the glorious forebear and the fatherly reference’ of their spiritual journeys.’8 Newman himself was a late convert to Catholicism from Anglicanism. It was his views on the role of emotion and subjectivity in conversion, and the prioritisation of conscience in religious matters, explored in his seminal essay, Grammar of Assent, that resonated with writers such as Oscar Wilde and Lionel Johnson:

Belief […] has for its objects, not only directly what is true, but inclusively what is beautiful, useful, admirable, heroic; objects which kindle devotion, rouse the passions, and attach the affections.

Newman continues, stating that ‘Conscience […] is something more than a moral sense; it is always, what the sense of the beautiful is only in certain cases; it is always emotional.’9 Newman described his own conversion as “like coming into port after a rough sea”,10 a maritime metaphor that is common among those who find peace in the Church after a period of agonising deliberation.

T.S. Eliot remarked in a letter to his friend, W.T. Stead (here paraphrased), ‘that he had an extraordinary sense of surrender and gain as if he had crossed a very wide, deep river, never to return.’11 It should be noted, too, that for many who choose to convert there is still a ceaseless internal struggle. The poet Lionel Johnson’s experience with Catholicism ‘appears to have been both a source of joy and the cause of a ceaseless internal struggle’.12

The Curious Case of Oscar Wilde:

The thought of Oscar Wilde concerning religion is varied and contradictory. Noel O’Mahony in his article, Oscar Wilde and the Church (1951) described Wilde as ‘at once sceptic and believer, cynic and sentimentalist, snob and anti-snob, pagan and admirer of Christ.’13 Wilde developed an intense interest in the Catholic Church during his time at Oxford. He once remarked to a friend, ‘I am not a Catholic…I am simply a violent papist’. An 1876 diary entry of Liberal MP, Ronald Gower, recalls a meeting he had with an Oxford undergraduate ‘[named] Oscar Wilde…a pleasant cheery fellow, but with his long-haired head full of nonsense regarding the Church of Rome. His room filled with photographs of the Pope and of Cardinal Manning’.14 In a letter to his friend, William Ward, Wilde confided that ‘I have dreams of a visit to Newman, of the holy sacrament in a new Church, and of quiet and peace afterwards in my soul’ (Murray, 9). I wonder how many admirers of Wilde’s work today are aware of these dimensions of his personality? For many, he is a poster-child of a libertine lifestyle and of the hedonistic approach to literature and art—all of which he certainly was. But he was not only that. He was also deeply conflicted, a restless seeker intent upon re-discovering the enchanted, romantic reality that was disappearing from modern life. Consider this excerpt from his 1891 essay, The Decay of Lying:

Now, everything is changed. Facts are not merely finding a footing-place in history, but they are usurping the domain of Fancy, and have invaded the kingdom of Romance. Their chilling touch is over everything. They are vulgarising mankind.

Towards the end of his life, especially after his prison sentence, his resolve seems to have strengthened. He held a brief audience with Pope Leo XIII in Rome in 1900, after which he wrote that “The Vicar of Christ has made me whole!”. During his time in prison, Wilde requested the works of Cardinal Newman and St. Augustine be sent to him, followed by a Greek New Testament. In his final days he was baptised and given the last rites by Fr. Cuthbert Dunne, a priest who later recalled that Wilde ‘repeated the prayers’ of contrition with lucidity. Wilde’s close friend at Oxford remarked that his conversion was not the desperate act of ‘a drowning man’, but in fact ‘a return to a first love […] one that had haunted him from early days with a persistent spell.’ This same spell haunted the literary figures of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries; leading many to wade the wide river of faith, despite the jagged rocks that often cut and scraped their soles beneath the waters.

Where to Now?

Like the Fin de Siècle writers of the late nineteenth century, we find ourselves treading water in a grey ocean of pleasure and muted melody, slipping beneath what Harold Bloom called ‘the tyranny of the visual’. We feel that we live in a kind of spiritual desert. Especially for those of us that are literary-minded, the ritual and heritage of the Catholic Church appears to be among the last vestiges of authentic enchantment in a thoroughly disenchanted world. After taking stock of our current situation, in the words of Anglican poet and priest, Malcom Guite, we find ourselves beginning the work of un-disenchanting ourselves. This un-disenchantment is enacted in many ways: in reading and memorising the great literature and poetry of the past (and present); in absorbing great works of art and music; and yes—albeit perhaps in the dark of our inner lives, largely away from the public eye—in the recovery of prayer and ritual. We are learning how to pray again. But in doing so, many of us rightly ask, Who is it that I am talking to? Louise Perry, a leading feminist voice in Britain, recently described herself in an interview with Glen Scrivener as an ‘agnostic Christian […] some weeks I believe, some weeks I don’t’.15 I believe this sentiment is more common than is generally acknowledged.

But for many of us, the process of returning to religion feels impossible, like trying to return to a pleasant dream after we have woken up by forcing ourselves back to sleep. We may fall asleep again, but we rarely find ourselves in the same dream. In life too, we feel that we have changed too much, that we know too much, to go back. The tragedy of the modern person is just that: outwardly he presents as a dispassionate agnostic, while in reality his religious and spiritual instinct has not gone away. It merely shows up elsewhere: in our poetry, our music, and our art. In the midst of this searching, many have found their rest in the Churches they once derided. Perhaps they understood, with piercing clearness, T.S. Eliot’s epiphany in the final lines of Little Gidding: that ‘the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.’

Footnotes:

https://nypost.com/2025/04/17/lifestyle/why-young-people-are-converting-to-catholicism-en-masse/

https://nypost.com/2024/12/03/us-news/young-men-are-converting-to-orthodox-christianity-in-droves/

Claire Masurel-Murray, Conversions to Catholicism Among Fin de Siècle Writers: A Spiritual and Literary Genealogy. 2012, p. 1.

Masurel-Murray, p. 3.

Masurel-Murray, p. 6.

Masurel-Murray, p. 7

Masurel-Murray, p. 2.

Masurel-Murray, p. 9.

John Henry Newman, An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, 1870. Ch. 5. As cited by Claire Masurely Murray in Conversions to Catholicism Among Fin de Siècle Writers: A Spiritual and Literary Genealogy.

John Henry Newman, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, p. 238.

Lord Harries of Pentregarth, The Conversion of T.S. Eliot. A transcript from a lecture delivered at Gresham College, 2018.

Claire Masurel-Murray, Conversions to Catholicism Among Fin de Siècle Writers: A Spiritual and Literary Genealogy. 2012, p. 7.

Noel O’Mahony, Oscar Wilde and the Church, 1951.

Aaron Taylor, Oscar Wilde’s Long Journey to Catholicism.Catholic Herald, 2018.

Glen Scrivener with Louise Perry. Speak Life. YouTube.

Can not a deep love, reverence, and respect for Nature be enough to satisfy the heart and mind, where one feels that she steps inside "Church" the moment she steps Outside? This is how it feels for me. It's nurturing and mystical, and it is Nature herself that causes me to write poetry. The purity and elevation of this experience is unlike anything I ever experienced in church, although I have to admit, I'm filled with the same appreciation and reverence whenever I step inside a "holy place." I think it's because I walked away from it all when I was younger, can view it now with fresh eyes, and feel that the "in there" and "out there" are now One and the same.

Love this piece. The world of religion, particularly Christianity is seeing a resurgence of similar nature to the one described, a reaching out for enchantment in a clinical and cynical era of cold science. I may be biased, as I’m not a traditional, church going Christian, but I don’t think Church is necessary to facilitate enchantment. I think one simply has to choose to be enchanted, choose to see the beauty of God’s creation and marvel and honour it by bringing others into that light. That could be through communion, conversation or through art & content like this.